Byron Clark

The Spark August 2010

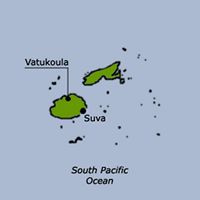

The Fiji Mineworke rs Union is currently seeking a resolution to one of the worlds longest running industrial disputes, over 340 workers have been on strike in the town of Vatukoula since 1991. In the 19 years since the strike began, the mine was closed (in 2006), sold, and re-opened under the ownership of another company, at which point none of the striking miners were re-hired. In recent times, gold production and sales have surged in Vatukoula while the former Emperor Gold employees continue to seek redress for their grievances. The miners continue to live in company housing and picket the mine regularly. The Spark examines the role the town of Vatukoula has played in Fiji’s labour history, and the exploitation of workers and the environment by multinational mining companies.

rs Union is currently seeking a resolution to one of the worlds longest running industrial disputes, over 340 workers have been on strike in the town of Vatukoula since 1991. In the 19 years since the strike began, the mine was closed (in 2006), sold, and re-opened under the ownership of another company, at which point none of the striking miners were re-hired. In recent times, gold production and sales have surged in Vatukoula while the former Emperor Gold employees continue to seek redress for their grievances. The miners continue to live in company housing and picket the mine regularly. The Spark examines the role the town of Vatukoula has played in Fiji’s labour history, and the exploitation of workers and the environment by multinational mining companies.

A Company Town

Gold was first discovered in the Vatukoula, in the north of Viti’ Levu by an Australian prospector in 1932, and the establishment of a mine by an Australian mining company, Emperor Gold Mining, followed soon after. Still a British colony, Emperor Gold practised what the Fiji Times has labelled “colonial-style mine management”. In a thesis submitted to the University of Vermont, Mary Ackley outlines what this means:

The mining company was initially able to secure an inexpensive migrant labor supply partially because of a British colonial protectionist policy that erroneously portrayed a comfortable rural Fijian subsistence economy, and thus allowed for the rationalization of low wages and temporary employment.

Ackley goes on to write that with the mining company owning all the land and housing, and monopolising employment in the area, “Vatukoula can truly be considered a company town.”

For decades Emperor Gold called the shots, but the workers began to get organised in 1960 when the company signed with the Fiji Mine Worker’s Union its first comprehensive agreement. In February 1977 the miners walked off the job, causing the board of directors to order the closure of the mine. That dispute was resolved with the intervention of the Ministry of Labour, but when miners again walked off the job in 1991 Emperor Gold followed through with its threat.

A History of Exploitation

In its decades of operation, Emperor Gold has given workers plenty of reasons to be aggrieved. When Fiji’s first Labour Party led government came to power in the 1980s, with the support of a militant organised labour movement, Emperor Gold chief executive Jeffrey Reid, a New Zealand stockbroker that The Age described as “ferociously anti-union” took a no holds barred approach to defending the company’s interests. Reid actively supported the 1987 coup that overthrew Fiji’s first multi-ethnic, working class aligned government. The coup stunted independent political development in a country with an electoral system divided on ethnic lines, a legacy of British colonial policy.

In a 2003 speech published in Pacific Ecologist, author of Labour and Gold in Fiji Dr ‘Atu Emberson-Bain stated that Reid’s support of the coup was “because for the first time the company faced the prospects of a government that was going to stand up for the indigenous mineworkers, and the Nasomo landowners.” According to Emberson-Bain “mining in Fiji is a low-wage industry. For much of our post-independence history in fact, average mine wages have lagged significantly behind those in other sectors like construction, transport and service sectors.” A miner in Fiji will earn only a quarter of what a miner in Australia will earn.

The strike

When on February 27 1991 miners walked off the job, Emperor sought and won a court injunction declaring the strike illegal. They went on to sack 436 workers in the following days. Riot police fed, housed and transported by the company, were brought to Vatukoula to secure company premises and evict sacked workers from their homes.

“The reasons for the strike were poor wages and the poor working conditions,” Usaia Seniu told aid organisation Oxfam, who investigated the situation in 2003 after a formal request from the Fiji Mine Workers Union. “I had no proper safety gear and sometimes loose rocks would fall and you needed to make sure that they did not fall on your head.”

The conditions miners were housed in were also appalling, company houses were made from corrugated iron and wood and had no bathroom or cooking facilities. Barracks built in the 1930s for single male workers, measuring six-by-four metres, housed entire families.

Since 1991, there have been near daily pickets of the mine’s main gate. In 1992, the striking miners marched demanding the immediate deportation of Jeffrey Reid.

Ecological impacts

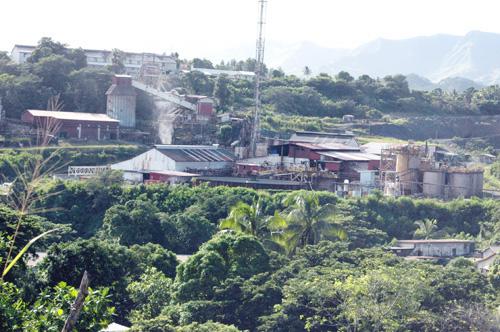

Pollution of air and water supplies caused by the mine has impacted on the health and well being of miners and their families, linking concerns about the natural environment with those about wages and working conditions. A major environmental audit in 1994 confirmed higher than safe levels of mercury and cadmium in water samples taken from the Nasivi River in Vatukoula.

Sulphur emissions were a major hazard. “The sulphur affects us all,” one ex-mine worker told Oxfam. “Every week or so when the wind changes the sulphur clouds come down. We see the cassava leaves burn and start to die off from the sulphur. It gives the children headaches and one six-year-old collapsed a couple of times from the sulphur. The sulphur collects on the roof and goes into the water tanks when it rains.”

International Solidarity

Robert Reid, general secretary of the National Distribution Union (New Zealand) and an executive member of the Asia-Pacific Regional Committee of the International Chemical, Energy and Mining Union Federation (ICEM) pledged solidarity, telling the Fiji Times:

The miners and their families have suffered severely over the last 19 years as the Emperor Gold Mine Company chose to close down the mine rather than negotiate a resolution of the issues with the FMU. I am sure that as other unions around the world hear that the struggle of the mine workers in Fiji continues they will also lend their support.

Australia’s Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union has recently stated that Australian mining companies operating in the Pacific ought to obey Australian regulations on safety and conditions. Peter Colley, national research director for the union called Emperor Gold a “fly by night operation.” telling Radio Australia, “Those sort of operations always like to have lower standards”.

In June the Vatakoula miners met with Fiji’s interim government and presented a compensation claim of $US4000 per miner for every year of the strike. The outcome of this meeting could be a significant victory for some of the Pacific’s most militant workers.

Just another WordPress site

I found this article really interesting and its about time more attention was brought to this problem. My partner is from Vatukoula so i have been hearing about the conditions there for a long time. We visited Vatukoula a couple of years ago and it was a truly sad experience. The locals have pretty much the same housing they used to in the 1960s and they are poorly maintained, though a friend is now living in a house that was once owned by one of the European managers.The vegetation in the area was covered with a thin layer of dust, the road in was in poor condition and the were no shops to speak of. It was clear the locals have hardly benefitted at all by the exploitation of such a valuable resource.

Hi, I’m the author of the University of Vermont thesis mentioned in this article and I’m glad to see this blogpost about Vatukoula. My husband and I also made a documentary film about the Vatukoula community, which also looks at how nearby Fiji Water has affected the community. You can learn more about the film, Rock of Gold, at http://www.rockofgoldfilm.com, and it will play at the upcoming American Public Health Association Annual Conference in Denver, CO this November.