– Mike Kay

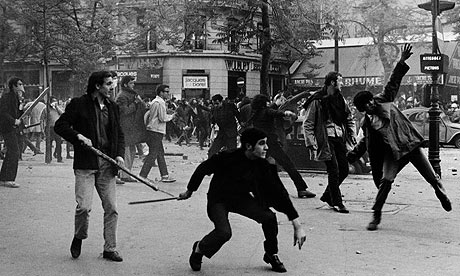

On May 1st 1968, Paris erupted. There had been a few big strikes in the years leading up to it, but by and large the upsurge took all by surprise.

It was the tenth anniversary of the day General De Gaulle had seized presidential power in France by an unresisted military coup. The parliament, feeling helpless to deal with the escalating war in Algeria, had voted over its powers to De Gaulle. The Fifth Republic that he established included wide-ranging presidential powers, reducing parliament to little more than a rubber stamp. During the Algerian war, protests were suppressed with lethal force.

The 1968 protests started with the students at Nanterre on the outskirts of the city. They had begun a campaign to visit each others’ rooms in halls of residence after 11pm, in defiance of their administration’s curfew.

Their campaign drew in students from all over France, who added their own grievances and demands. The immediate issues were the dereliction and overcrowding of universities, which were bursting at the seams due to the trebling of the number of students in less than a decade, and the government’s plans to impose exams in order to reduce the numbers of first-year students.

Violent state repression only served to spread the movement. The daily demonstrations and occupations soon inspired workers to strike in industries from car production to banking. The workers’ demands were at first minimal – for wage concessions and greater social security. However, as a mass strike wave developed and continued throughout May, many long-germinating working-class aspirations came to the fore and began to lead to much more revolutionary demands.

It quickly became clear that the government was unable to control the situation. De Gaulle had initially written off the protests as a sectional student concern. Now, workplaces across France were being occupied by strikers, and people from all walks of life were coming together to enthusiastically debate the shape of the new society they wanted.

At the peak of the general strike, on May 25th, there were between eight and ten million strikers. Yet there was still no national instruction coming from the union leaders. And there was to be none – at least, not until they decided to bring the movement to an end.

The apparatus of the Communist Party’s union, the CGT, organised the return to work. The greatest resistance that it faced was in the large production industries. For instance, at the Renault-Flins factory, where the workers were younger and mostly unskilled, the CRS (military riot police) occupied the plant on June 7th, in an attempt to break the strike. For two days there were violent confrontations between the police on the one hand, and the strikers and students on the other – a 17-year-old Maoist high-school student, Gilles Tautin, was killed, drowned in the river Seine by the CRS.

The revisionist Communist Party sold out the movement, but they were by far the largest force on the left and still well-respected by older workers. The revolutionary groups were tiny, and many of them had written off the working class in the industrialised countries as a spent force before May 1968.

The far left was also largely student-based, lacking real roots in the factories. Had it gained credit in the eyes of a significant layer of workers, it might have acted as a counterweight to the treachery of the Communist Party.

The other lesson to draw from May 1968 is that the uprising was not the result of any kind of economic crisis. Workers’ living standards had been rising for years (although inequality was widening) and society seemed very stable. Even in apparently quiet times, like the present, the potential for mass rebellion lurks beneath the surface of society.