Phil Ferguson

The Spark May 2010

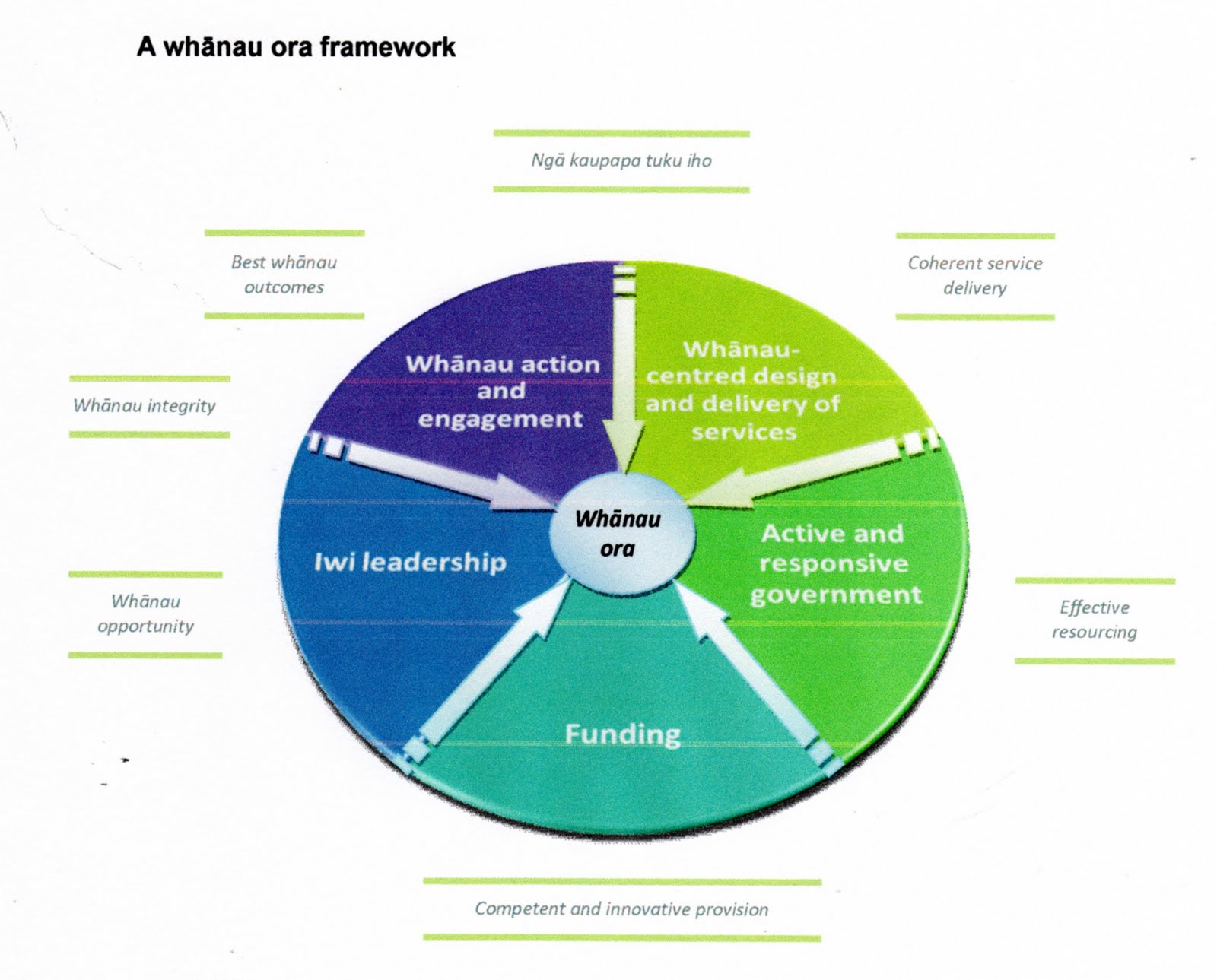

On April 21, the report of the government-commissioned Whanau Ora taskforce was made public. The key idea of Whanau Ora (“Well-being”) is the establishment of a one-stop- shop approach to the problems of  individuals and families in relation to problems of health, education and the justice system. Funds are to be diverted from existing stage agencies into a new Whanau Ora Trust which would contract out work to service providers to deal with the problems on a whanau basis. In other words, where an individual family member had health, education or justice system problems, the individual would be viewed as part of their whanau and the whole whanau would be engaged in finding solutions. This is seen as “empowering” both whanau and individual Maori.

individuals and families in relation to problems of health, education and the justice system. Funds are to be diverted from existing stage agencies into a new Whanau Ora Trust which would contract out work to service providers to deal with the problems on a whanau basis. In other words, where an individual family member had health, education or justice system problems, the individual would be viewed as part of their whanau and the whole whanau would be engaged in finding solutions. This is seen as “empowering” both whanau and individual Maori.

Although Whanau Ora was originally conceived by its Maori Party architects as a programme for Maori, there is now agreement that all “families in need” will have access to the services provided through the programme.

Much is being made of the potential for Whanau Ora by the Maori Party and a layer of Maori community activists, as well as by members of the National Party government. According to Te Runanga o Ngati Whatua chair Naida Glavish, for instance, Whanau Ora is “one of the most significant milestones in the history of Maori in this country since the signing of the Treaty.” National deputy prime minister and finance minister Bill English thinks it has the potential to provide the government with “better value for money” and that its principles “ask the right questions and look for some hard answers”. English joined Maori Party co-leader and proposed Whanau Ora minister Tariana Turia at Te Puni Kokiri in the public launch of the taskforce report.

At present, there is very little in the way of specific detail. What is clear, however, is the overall social, economic and political position of Maori today. This position, however, is rather more complex than it is often treated as by the left. Much left discourse on Maori oppression repeats things that were true thirty and more years ago, but simply doesn’t analyse the changes that have taken place both in the operations of capitalism in this country and the position of Maori within those operations.

CHANGES FOR THE BETTER Statistics for Maori have improved since the shift from socially and economically rural agriculture to an urban working class existence, following World War Two. Maori life expectancy increased dramatically in the 1920s and 1930s, and has continued to do so – life expectancy for Maori women is now 75.1 years (an increase of almost 20 years since the early 1950s) and for Maori men, 70.4 years (an increase of about 16 years since the early 1950s). Maori average weekly income has risen from $486 in 1998 to $722 in 2008 and Maori average weekly income for 15-24 year olds is now higher than for pakeha of the same age ($506 compared to $464), although this also reflects the proportionately higher number of young pakeha in tertiary education. Nevertheless, the numbers of Maori in tertiary education have also risen substantially. The number of Maori who are now in small business and self-employed has been growing at a faster rate than any other ethnic group. In the period from 2001 to 2006, for instance, Maori self-employed grew by 20%, compared to 8.8% for non-Maori. Compared to employed Maori, there is also a greater percentage of self-employed Maori in the $50,000 and over income bracket. The shift into higher income brackets in those same years for self-employed Maori (13%) is higher than for self-employed non-Maori (10%).

Maori have also been moving up the job ladder. Between 2003 and 2008 there was an almost 26% increase in the number of Maori in high-skilled occupations and a 33% increase in the number of Maori in skilled occupations, while the numbers in low-skilled and semi-skilled occupations scarcely changed. Almost two in five Maori are now in skilled and high-skilled occupations. The number and scope of Maori employers has also being growing noticeably. Between 2001 and 2005/6, the number of Maori employers rose by 1536 or 28%, while across the population as a whole the increase was only 10%. In terms of entrepreneurial activity Maori (17.7%) were surpassed globally in the 2001-2005 period by just two countries. Maori women have the world’s third highest rate of entrepreneurialism. In 2001, Maori-owned commercial assets were $8.9 billion; in 2005/6 they amounted to $16.5 billion.

The 2003 Maori Economic Development Report noted that the Maori economy is more profitable than the New Zealand economy overall and its rate of growth has generally exceed the rate of growth of the total economy since the end of the 1980s. Maori are net lenders to the rest of New Zealand and also pay a bit more in tax than they receive in benefits.

Most of this is very different from even the period of the long economic boom after WW2. During that time Maori, although their incomes and health statistics improved substantially, were still concentrated in the manual workforce and there was little in the way of a Maori middle class, let alone a Maori capitalist layer.

These changes of the past 20-25 years are linked to a new discourse about Maori advancement. Whereas even twenty or thirty years ago discourse on Maori advancement, let alone liberation, was either anti-capitalist or involved some kind critique of aspects of capitalism, the discourse on Maori advancement today is dominated by ideas of entrepreneurship and Maori capitalism. Indeed, according to a recent report Te Puni Kokiri commissioned from the New Zealand Institute for Economic Research, there is now “a Maori edge” – “it’s cool to be Maori” and so Maori business making and selling things that can be presented as “authentically” Maori have a competitive advantage in the market place. Instead of the success of pakeha business leading to a trickle-down effect for Maori, the argument is now that Maori business will create a flow-on effect for the wider NZ economy.

THE OTHER SIDE OF THE PICTURE While the kind of figures cited above certainly reflect important trends in the position of Maori in this country in the twenty-first century, they only form part of the picture. The other part of the picture is that Maori, on average, remain worse off than pakeha. Maori average hourly wage rates have grown more slowly than average wage rates in general – for instance, Maori average hourly wages rose from $14.33 in June 2002 to $17.58 in June 2007, but economy-wide hourly wages increased from $16.71 to $21.41. As of June 2009, Maori were three times more likely to be unemployed than pakeha. Maori life expectancy, despite a substantial increase is still 5-10 years behind pakeha life expectancy and maori are still incarcerated at far higher rates than pakeha, making up a vastly disproportionate number of the prison population. The fact that Maori are a lot more likely to be doing time for dishonesty offences such as burglary and car conversion than pakeha indicates the youthfulness of the Maori population, that it remains disproportionately working class and that judges are more likely to lock up young working class people, especially brown-skinned ones, than middle class crooks, especially white ones.

Moreover, while there is now a substantial Maori middle class and a Maori capitalist layer at the other end of the pyramid of Maori capitalism is an impoverished and alienated section of Maori. Many of the newly-impoverished and alienated Maori are in families which were once sustained by often relatively good-paying jobs in the meat works, transport and the timber industry. Whole communities of Maori (and pakeha) workers were created around these jobs. There was social cohesion, people saw themselves as part of a community of workers and helped each other out in times of economic stress, stuck together during industrial disputes, helped each other with DIY projects and so on. The economic reforms of the fourth Labour and National governments destroyed many of these jobs and communities. They took away not only the incomes from those jobs, but also the social solidarity that existed in those communities.

THE SOLUTIONS OF OUR RULERS Ever since then one of the key policy concerns of the state and the ruling class has been how to manage the anti-social consequences of those economic reforms. It’s not that they care about the people themselves; but they do care about the fallout when it results in increases in crime and general social problems. The state and the ruling class are smart enough to know that police truncheons, while certainly used on working class youth (especially brown-skinned working class youth) are by themselves woefully inadequate. Much more sophisticated mechanisms of control are needed. The main ones revolve around using upwardly-mobile Maori to manage the Maori so-called “underclass” (ie the most downtrodden section of working class Maori who have been dispossessed of jobs, economic independence, a sense of community and working class social solidarity and have partly disintegrated personally and collectively under such circumstances, resulting in increases in anti-social activity against fellow working class people and any forms of activity which make the middle and upper classes nervous). The state, however, also doesn’t want to spend too much money managing the so-called under-class which has been created by the operations of the very social system the state defends.

These factors, along with the state’s desire to help the development of Maori capitalism, shape state policy towards those at the bottom of the socio-economic heap. It’s within this context that Whanau Ora comes into existence. It’s essentially about managing the damage done by the very socio-economic system which the leadership of the Maori Party have embraced and wish to help run. And enriching Maori service providers in the process .

Class divisions have become more pronounced among Maori and the more pronounced they have become the more middle and upper class Maori have been attempted to put their own interests forward as those of Maori in general, obliterating Maori working class voices in the process. Because the core problem is not “colonisation” and the loss of Maoritanga, but the perfectly normal operations of a capitalist system long past its best-by date, neither Whanau Ora nor any other approach within the confines of the existing system is going to be able to turn the situation of the most desperate working class familiesaround.

SOLUTIONS OF HOPE This, however, doesn’t mean things are hopeless. In 1979 a radical, socialist-inclined movement called the New Jewel Movement took power, via a revolution, in the small Caribbean country of Grenada. The country had been run by a corrupt dictatorial regime and anti-social activity on the part of the oppressed was quite widespread. Within a year, inter-personal violence (assault, murder), robbery and other anti-social activity had almost disappeared. The reason was that the revolutionary process united people and created social solidarity and hope in place of the war of all against all which is a typical feature of capitalist society.

Only forms of action which challenge the system, unite people in struggle and therefore create genuine forms of social solidarity and real hope, can turn around the problems facing the most distressed working class areas in the country and the people most broken-down by the oppressive and divisive nature of capitalism.

Just another WordPress site