Mike Kay

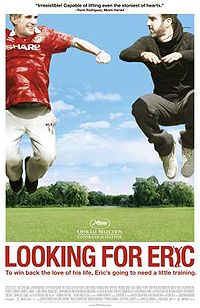

“It all began with a beautiful pass from Eric Cantona.” So begi ns the latest film from socialist film maker Ken Loach.

ns the latest film from socialist film maker Ken Loach.

From the movie’s outset, it is clear that Eric the postie is languishing in life’s relegation zone: estranged from his wife, unable to handle his teenage tearaway stepsons and contemplating suicide. In desperation, he raids his stepson’s marijuana stash, and after a couple of crafty tokes, he is astonished to discover that footballing legend Eric Cantona has appeared in his Manchester United-adorned bedroom. Cantona then proceeds to dispense considerate advice along with soupçons of his Gallic philosophy.

Unsure whether he is finally losing his mind, Eric the postie nevertheless finds his new-found acquaintance with his hero is bringing positive change to his life. Meanwhile, his postie mates form an entertaining comic ensemble. But things take a decidedly dark turn when his stepson becomes enmeshed in the schemes of a ruthless gangster who owns a flash SUV and an executive box at United. His individual attempts to confront the hoodlum are hopeless. Only when he and his workmates put their heads together is there any cause for optimism.

Discussing his film, Loach indicated his desire to make a movie that was “less ostensibly political, more kind of a relationship story.” He also explained the attraction of the project to Cantona: “I think he is very wary of being drawn into overtly political organisation, but I think in a general sense he is in favour of the interests of ordinary people. His roots are in the working class culture of Marseilles. His grandparents, of whom he is inordinately proud – and rightly so – fought for the Republicans against Franco in Spain.”

As someone who has worked on the Post in Britain for seven years I can attest to the authenticity of Loach’s depiction of the workers: the obsession with football, the camaraderie of the sorting office and pub lounge, the endless piss-takery. But a single aspect is curiously absent: the continual, sometimes intense, class struggle that conditions the job. When Eric the postie recalls Cantona’s glory days with United in the mid-90s, that was also a period of full-on industrial action in response to management changes intended to increase the commercialisation of the Post Office. Many of the same issues (job cuts, “flexibility”) lay behind the return of nation-wide strike action last year.

Of course Ken Loach is not obliged to emphasise that aspect simply because he is Ken Loach. But the fact that there is not even a passing reference to the posties’ famed militancy smacks of self-censorship.

No doubt, “Looking for Eric” is a more commercial film than some of Loach’s other offerings. But looking back over his body of work, one could say that this fairly simple tale of standing up to the local bully is closer to his allegorical film “Raining Stones” than a more “didactic” movie like “Land and Freedom”.

As the credits roll, the message of the film is pretty clear: these are dark days where the powerful seem invincible and the oppressed appear feeble, but don’t give up hope, “trust your team mates”, act collectively and you can win the day.

“It all began with a beautiful pass from Eric Cantona.” So begins the latest film from socialist film maker Ken Loach.

From the movie’s outset, it is clear that Eric the postie is languishing in life’s relegation zone: estranged from his wife, unable to handle his teenage tearaway stepsons and contemplating suicide. In desperation, he raids his stepson’s marijuana stash, and after a couple of crafty tokes, he is astonished to discover that footballing legend Eric Cantona has appeared in his Manchester United-adorned bedroom. Cantona then proceeds to dispense considerate advice along with soupçons of his Gallic philosophy.

Unsure whether he is finally losing his mind, Eric the postie nevertheless finds his new-found acquaintance with his hero is bringing positive change to his life. Meanwhile, his postie mates form an entertaining comic ensemble. But things take a decidedly dark turn when his stepson becomes enmeshed in the schemes of a ruthless gangster who owns a flash SUV and an executive box at United. His individual attempts to confront the hoodlum are hopeless. Only when he and his workmates put their heads together is there any cause for optimism.

Discussing his film, Loach indicated his desire to make a movie that was “less ostensibly political, more kind of a relationship story.” He also explained the attraction of the project to Cantona: “I think he is very wary of being drawn into overtly political organisation, but I think in a general sense he is in favour of the interests of ordinary people. His roots are in the working class culture of Marseilles. His grandparents, of whom he is inordinately proud – and rightly so – fought for the Republicans against Franco in Spain.”

As someone who has worked on the Post in Britain for seven years I can attest to the authenticity of Loach’s depiction of the workers: the obsession with football, the camaraderie of the sorting office and pub lounge, the endless piss-takery. But a single aspect is curiously absent: the continual, sometimes intense, class struggle that conditions the job. When Eric the postie recalls Cantona’s glory days with United in the mid-90s, that was also a period of full-on industrial action in response to management changes intended to increase the commercialisation of the Post Office. Many of the same issues (job cuts, “flexibility”) lay behind the return of nation-wide strike action last year.

Of course Ken Loach is not obliged to emphasise that aspect simply because he is Ken Loach. But the fact that there is not even a passing reference to the posties’ famed militancy smacks of self-censorship.

No doubt, “Looking for Eric” is a more commercial film than some of Loach’s other offerings. But looking back over his body of work, one could say that this fairly simple tale of standing up to the local bully is closer to his allegorical film “Raining Stones” than a more “didactic” movie “Land and Freedom”.

As the credits roll, the message of the film is pretty clear: these are dark days where the powerful seem invincible and the oppressed appear feeble, but don’t give up hope, “trust your team mates”, act collectively and you can win the day.