The following article, published on November 1, 2006, was written by John Riddell, then a co-editor of the now ceased Socialist Voicewhich was produced in Canada. We are publishing it in two parts. Part one, here, appeared in the July issue of The Spark and part two will appear in the August issue.

When Bolivian President Evo Morales formally opened his country’s Constituent Assembly on August 6, 2006,

he highlighted the aspirations of Bolivia’s indigenous majority as the central challenge before the gathering. The convening of the Assembly, he said, represented a “historic moment to refound our dearly beloved homeland Bolivia.” When Bolivia was created, in 1825-26, “the originary indigenous movements” who had fought for independence “were excluded,” and subsequently were discriminated against and looked down upon. But the “great day has arrived today … for the originary indigenous peoples.” (http://boliviarising.blogspot.com/1, Aug. 14, 2006)

During the preceding weeks, indigenous organizations had proposed sweeping measures to assure their rights, including guarantees for their languages, autonomy for indigenous regions, and respect for indigenous culture and political traditions.

This movement extends far beyond Bolivia. Massive struggles based on indigenous peoples have shaken Ecuador and Peru, and the reverberations are felt across the Western Hemisphere. Measures to empower indigenous minorities are among the most prestigious achievements of the Bolivarian movement in Venezuela.

At first glance, these indigenous struggles bear characteristic features of national movements, aimed at combating oppression, securing control of national communities, and protecting national culture. Yet indigenous peoples in Bolivia and elsewhere may not meet many of the objective criteria Marxists have often used to define a nation, such as a common language and a national territory, and they are not demanding a separate state. Continue reading “The Russian Revolution and National Freedom: How the early Soviet government led the struggle for liberation of Russia’s oppressed peoples”

WHAT IS MARXISM?

A talk by Don Franks, Marxism 2010 conference, Wellington 5 June 2010

This is obviously a big subject, which could be approached in a number of ways. In the small time we have this morning, my aim will be to introduce basic points and hopefully arouse some ongoing interest.

Ther e are various contending definitions of ‘Marxism”. The one I’m tempted to offer today is that Marxism is a set of sharp political tools, which New Zealand leftists tend to leave in the box. Later on in this talk I’ll consider why that has been so frequently the case.

e are various contending definitions of ‘Marxism”. The one I’m tempted to offer today is that Marxism is a set of sharp political tools, which New Zealand leftists tend to leave in the box. Later on in this talk I’ll consider why that has been so frequently the case.

As a more general definition to introduce Marxism, I’ll add that it’s a theory named for its main architect and can be understood as the theory of dialectical materialism based on communist practice. The expression ‘dialectical materialism’ has a forbidding sound and is not common currency in the day-to-day life of most people. Here I see a huge contradiction, because dialectical materialism is a thoroughly practical method of understanding human society and the universe in which we’re placed. Dialectical materialism is also a philosophy which by its nature takes sides with the oppressed. Continue reading “WHAT IS MARXISM?”

OPEN BORDERS OR LEFT NATIONALISM?

History

by Don Franks

Since its formation the Workers Party of New Zealand has recognised that immigration controls are essentially a boss’s device to control workers. Accordingly, the Workers Party has always stood firmly in opposition to immigration controls. Point 4 of our 5-point programme spells it out in these words:

“For working class unity and solidarity – equality for women, Maori and other ethnic minorities and people of all sexual orientations and identities; open borders and full rights for migrant workers”.

Some people see our policy of open borders as extremist. Others realise that a truly internationalist position can’t settle for anything less. Genuine socialists insist on workers absolute freedom to travel and take up residence wherever they choose. Continue reading “OPEN BORDERS OR LEFT NATIONALISM?”

Review: Teamster Rebellion

Teamster Rebellion is a classic, and highly recommended for anyone interested in strengthening the union movement as we head into recession. First in the Teamster series, this compelling account of the 1934 strikes in Minneapolis sheds light on the rewards of worker militancy. Author Farrell Dobbs was one of the central leaders at the time, and he lays out the various strategies and pitfalls of the strike with admirable clarity.

Dobbs makes it clear that the biggest setback for workers in the Great Depression was a bureaucratic union movement. In fact, membership in unions actually declined in the early days of the Depression. Dobbs describes the “business unionism” of the American Federation of Labour, involving strict division of crafts, a minimum of strikes and suppression of dissidence.

Communist Party of the Philippines’ 40th anniversary

The Workers Party of New Zealand sends warm greetings to the Communist Party of the Philippines, on its 40th anniversary.

The CPP has led the struggle against feudalism, capitalism and imperialism in the Philippines for four decades. Having withstood the Marcos dictatorship through to the current brutal regime of Arroyo, the CPP has been sustained through its deep roots among the masses. When many other communist parties around the world collapsed in the 1990s, the CPP carried on the struggle, constantly reassessing itself and further developing its strengths.

The CPP’s commitment to internationalism has given confidence to many organisations and individuals in the struggle for world revolution.

We hope that 2009 will bring much success to the comrades in the Philippines.

In solidarity

Workers Party of New Zealand

A far left reply to Chris Trotter

– Don Franks, Workers Party candidate for Wellington Central 2008

The Dominion Post warns of a malicious workers’ enemy currently lurking in New Zealand.

What “it” supposedly “wants to see (on workers tables) are scraps of stale bread and cups of cold water.” Along with “the power and the phone cut off, holes in the roof, and the car up on blocks in the front yard.”

“Nothing delights it more than the sight of padlocked factory gates, and the sobbing of laid-off workers is music to its ears.”

According to Dominion Post columnist Chris Trotter, this inhumanity embodies none other than the revolutionary component of the political left. He specifically cites the Workers Party as an example.

According to Trotter:

“The more the National Party cuts back and hacks away at the workers’ economic and social rights the better the revolutionaries like it.

“The far Left is always at its unhappiest when Labour is in power. In no time at all they’ve got the power and the phone reconnected, filled up the fridge, got a bit of a fire going in the grate, slipped a couple of pizzas in the oven, and cracked open a few cool ones.” (From The Left, Dominion Post 12/12/2008)

Chris may have forgotten that it was under Labour that Mrs Folole Muliaga tragically lost her life when her power was cut off.

Marx in the 21st century

Talk given by Tim Bowron at a public forum at the Christchurch WEA in November 2008 organised by the Workers Party.

It seems as though these days the only time you are likely to hear the name of Karl Marx mentioned is when he is being dismissed as the proponent of some outlandish utopian ideology which had marginal relevance in nineteenth century Europe but none at all now (the view of most standard history texts) or as a the prophet of capitalist globalisation who also had some rather funny ideas about workers and exploitation with which we need not concern ourselves too much (the view of more sophisticated bourgeois pundits such as the writers for The Economist).

It is indeed true that the idea that the working class of which Marx wrote so volubly is rapidly vanishing from the stage of history has some material basis (at least in first world countries like New Zealand). However while the number of workers directly engaged in the creation of surplus value in areas such as manufacturing and raw material extraction has certainly decreased in New Zealand over the past few decades, the amount of exploitation i.e. the mass of surplus value created by workers in these sectors and expropriated by the capitalists has not.

In addition, although the largest occupational group as measured in the 2006 New Zealand census were labelled as “professionals” (18.85%) followed by “managers” (17.14%), the relationship of these individuals to the means of production is clearly shown in the “status in employment” category where we learn that over 75% of the population are still dependent on selling their labour power in order to earn a living.

The real problem here then is not the absence of class but rather the collapse of working class consciousness (such that a supermarket checkout supervisor may now well consider themselves a “manager”, and various politicians can proclaim that we are “all middle class now”).

40 years on: The 1968 Mexican student rebellion

– Tim Bowron

Orginally published at Socialist Democracy.

The situation in most of Latin America in 1968 was vastly different to that in Europe, the United States and South East Asia. Throughout most of the continent the revolutionary dynamic seemed to be running in reverse – since the 1959 Cuban Revolution the left seemed to be everywhere on the retreat, with right-wing military dictators ruthlessly crushing any opposition.

It was not as though the left suffered from any shortage of militancy – in Venezuela and Colombia communist cadre inspired by the example of Ernesto “Che” Guevara fought heroically to overthrow capitalism by setting up guerrilla foco in the countryside. However unlike their Cuban comrades they failed in the vital task of building a parallel mass underground movement among the urban working class, and consequently were left isolated.

An attempt by Guevara himself to lead a guerrilla insurgency in Bolivia in similar conditions led to his capture and execution at the hands of local military and US intelligence officers in 1967.

In Peru the peasant leader Hugo Blanco had led a relatively successful guerrilla campaign in the early 1960s which had mass support among the indigenous population of the Cuzco region, but by the mid 60s Blanco was in jail and the insurgency crushed.

In 1968 a left-wing army officer named General Juan Velasco Alvarado took power in Peru in a coup d´état, however despite implementing land reform and some other progressive measures the workers and peasants continued to be marginalised under his regime.

In Argentina too a military regime was in power throughout the period and the left driven largely underground for most of the decade. Only in 1969 would the class struggle briefly reassert itself with the urban uprising known as the Cordobazo.

However, in the continent of Latin America there was one key flashpoint in 1968 – Mexico.

Continue reading “40 years on: The 1968 Mexican student rebellion”

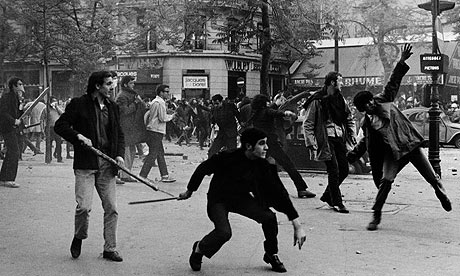

France 1968 – on the brink of revolution

– Mike Kay

On May 1st 1968, Paris erupted. There had been a few big strikes in the years leading up to it, but by and large the upsurge took all by surprise.

It was the tenth anniversary of the day General De Gaulle had seized presidential power in France by an unresisted military coup. The parliament, feeling helpless to deal with the escalating war in Algeria, had voted over its powers to De Gaulle. The Fifth Republic that he established included wide-ranging presidential powers, reducing parliament to little more than a rubber stamp. During the Algerian war, protests were suppressed with lethal force.

The 1968 protests started with the students at Nanterre on the outskirts of the city. They had begun a campaign to visit each others’ rooms in halls of residence after 11pm, in defiance of their administration’s curfew.

Their campaign drew in students from all over France, who added their own grievances and demands. The immediate issues were the dereliction and overcrowding of universities, which were bursting at the seams due to the trebling of the number of students in less than a decade, and the government’s plans to impose exams in order to reduce the numbers of first-year students.

Violent state repression only served to spread the movement. The daily demonstrations and occupations soon inspired workers to strike in industries from car production to banking. The workers’ demands were at first minimal – for wage concessions and greater social security. However, as a mass strike wave developed and continued throughout May, many long-germinating working-class aspirations came to the fore and began to lead to much more revolutionary demands.