Joel Cosgrove

Joel Cosgrove

Universities are an important part of modern society. The Education Act of 1989 defines them as being the “critic and conscience of society”. In practice the record has been patchy at best. Students (and staff) have historically joined in repressive actions against striking wharfies in 1913, deputised and moblised to put down peaceful marches by unemployed workers during the depression.

In the documentary 1951 author Kevin Ireland recalls calling a Student Representative Council meeting to make a stand against the draconian laws passed to smash the locked out watersiders in 1951 and finding his progressive motions drowned out 10-1 by conservative students, bent on supporting the authoritarian actions of the state. Future Prime Minister and editor of the Victoria University student newspaper Salient described the (relative) progressive freedoms in place for women at the university in the mid-60’s as corrupting, stating that “If she does this [get involved in politics] she will never become a lady” as well as becoming losing their apparent “femininity”. Michael Laws first came to prominence at Otago University as a leading supporter of the Springbok Tour, with surveys at both Otago and Victoria Universities indicating a rough 50/50 split in opinion for and against the tour. Even during the ‘golden years’ (roughly the 1960’s-80’s) the role of the university was to pump out industry friendly graduates. Every freedom gained, was gained through struggle. Some of the early protests in the 60’s at Victoria University were over the right for students to have the ability to live in mixed gendered flats.

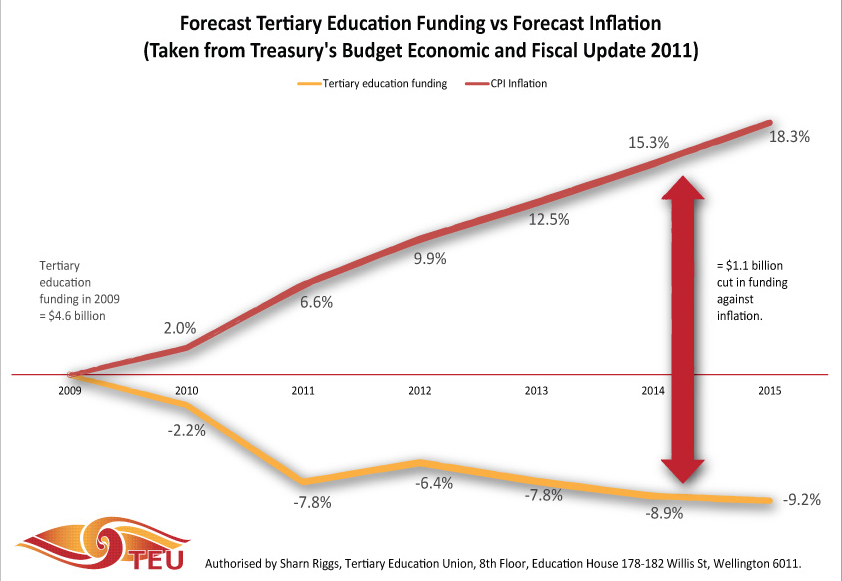

Per capita funding for universities rose in real terms through to the mid-70’s and since then has been declining. To an extent this reflects a much broader uptake of tertiary education in the 90’s than in the 70’s in part due the privatisation of a lot of training that used to be done on site, off to various tertiary institutes i.e. bar hospitality courses, trades training, pushing the cost onto the worker, with no promise of actual employment. As well as that a falling rate of profit and the general crisis of capitalism that occurred in the mid-70’s in tandem with the turn to neoliberalism, undermined any ability to continue the same level of supply for the increased demand.

Initially the various institutions absorbed the increasing costs. But eventually in 1990 Phil Goff, as Minister of Education under the 4th Labour Government, introduced a flat $1200 fee. The role of fees and commercialisation has been to make up for the shortfall in funding received from government. Over time they have become a larger and larger section of the whole cost of providing education, becoming a greater barrier to those from working class backgrounds or those who can’t guarantee a well paying job at the end of study with which to pay off the now ubiquitous student loan.

Right now at Victoria University budgets have been slashed, pay rises are below inflation, resourcing cut, tutor numbers have fallen dramatically and more people are being crammed into each course. Subjects like teaching or foreign languages (subjects which require relatively large amounts of one-to-one interaction between lecturer and student) are either being phased out or pressured to adopt a lecture theatre mentality, something that involves far less personal interaction. Much like the present National Government, VUW Management have made ‘soft’ cuts i.e. fewer contract tutors, bigger classes, fewer resources. In the next few years, they are going to run out of ‘soft’ options and be forced to fire large numbers of staff and cut back on many important programmes. This situation is being repeated all over the country. The less easily commercialised a course is, the more danger it is in.

The prevailing tertiary funding policy in the 90’s and 00’s was known as ‘Bums on Seats’, institutions were funded based on numbers of students or Equivalent Full-Time Students (EFTS). So if Sociology and Anthropology (the popular courses in my first year) are popular then they get more funding, if they lose popularity then they lose funding. Academic research played little role in these formulations.

In the early 00’s the then Labour Government (with a large involvement by current Deputy Leader Grant Robertson) brought in the Performance Based Research Fund (PBRF), a process that operates alongside the EFTS model which prioritises and grades research work. In the same way that the NZ on Air funding model is accused of creating through its funding structure the narrowed environment that funds bands such as the Feelers, Autozamm, Six60 etc. so PBRF is accused of narrowing and determining what research is valued, what is not and how it is.

The 90’s were full of scandals about desperate institutions gaming the system by inflating their numbers through junk courses, the same process is underway with academic research. In Auckland University, the struggle currently focuses around management’s attempts to create a two-tier structure of research academics and teaching lecturers. The current collective agreement provides research leave for all academics, this allows first year students to be taught by world-leading academics in their field, however in the pursuit of commercialisation, this is not seen to be beneficial. In the same spirit, the position of Professional Teaching Fellows (PTFs) has been created as a way of pushing through this agenda, alongside a refusal to sign a collective contract that doesn’t deliver on these demands. These roles are generally fixed term and are not placed on any step or salary scale. This is not a new trend, a lecturer at Gender and Womens Studies at VUW was on a revolving fixed-term contract for over ten years. This is just taking that process to a higher level.

The current government budget process is based on the assumption of on average 1.1% yearly pay increase for the foreseeable future. The commercial reality of the modern university is that 5% yearly fee increases are not enough to cover the growing shortfall in government funding.

We need to take back the University. But the University is placed firmly within society. It is no ivory tower. It is funded through the exploitation of workers, many of whom are studying as well. The university could not exist without the wider support of society. Yet like every other part of society, it is constrained by the pressure of the capitalist profit motive. Universities are not structured to serve society at large, but to replicate the inequalities that exist around us.

We need to take back the University. But the University is placed firmly within society. It is no ivory tower. It is funded through the exploitation of workers, many of whom are studying as well. The university could not exist without the wider support of society. Yet like every other part of society, it is constrained by the pressure of the capitalist profit motive. Universities are not structured to serve society at large, but to replicate the inequalities that exist around us.

The pressure is mounting. Only a wider revolutionary movement that sees the University as a part of society as a whole can really free it from the current dead end street. The first steps are to fight the cuts, fight the layoffs and to stop the further attacks on conditions, courses and access.

For more reading:

Can students be radical?, Workers Party

Students and the Education Factory, Socialist Worker

Just another WordPress site