By Te Ringa Mangu (Dun) Mihaka & Diane Patricia Prince

By Te Ringa Mangu (Dun) Mihaka & Diane Patricia Prince

Ruatara Publications, 1984

Reviewed by Mike Kay, Workers Party Auckland and The Spark editorial board. This article first appeared in the April issue of The Spark.

As the media ramps up the hype around the Royal Wedding on April 29, now seems like a good time to revisit a period in New Zealand history when there was a republican movement willing to take militant action against the Monarchy.

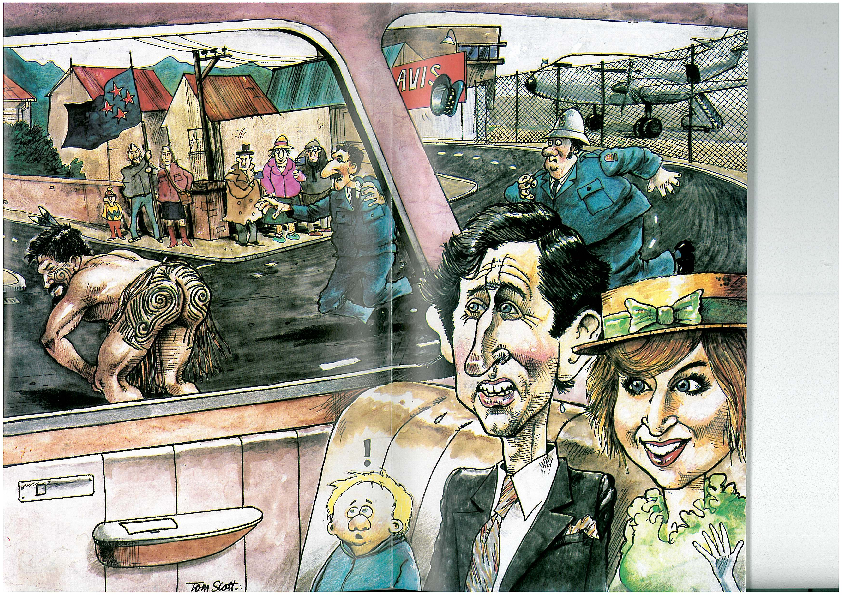

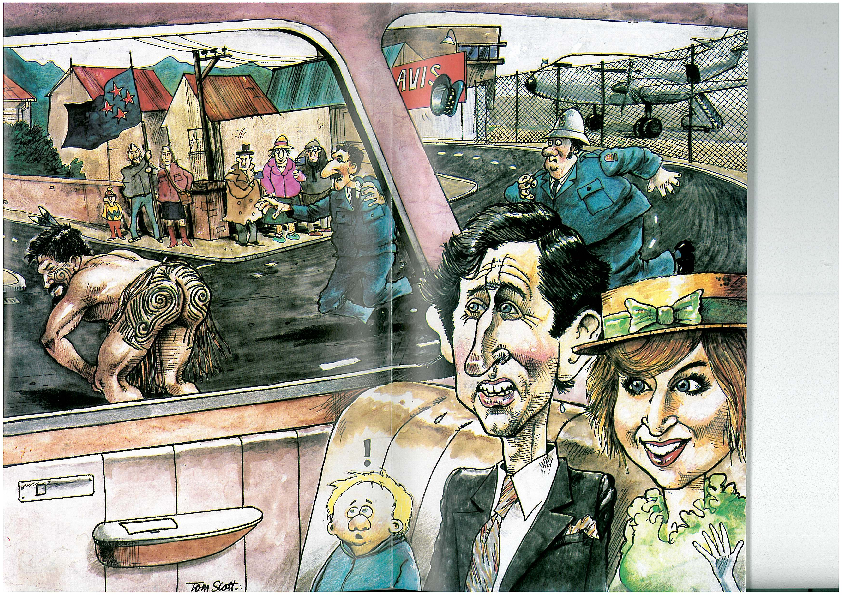

During the 1983 Royal Tour of New Zealand by Prince Charles, Diana Princess of Wales and their infant son William, Dun Mihaka achieved international notoriety by performing a “whakapohane i te tou” (baring of the buttocks) in front of the Royal limousine as it exited Wellington Airport. He was immediately arrested following his protest. The brutality of the arrest (two police officers forced him to the ground) provoked his confidante and wife, Diane Prince, to attack the police, and she herself was taken into custody. This book is essentially the story of the resulting trial. The authors have left us with a superb example of how to present a political trial; they effectively put the whole system – police, courts, media, politicians and the Monarchy itself – on trial.

Conducting his own defence, Mihaka displays a refreshing lack of deference to judges and police officer witnesses. He sets out the purpose of the book thus: “if we hadn’t have done it [the protest], we would not have been able to bring you this blow by blow account of why it was done, the profound historical, cultural and social implications of the act itself, and the reasons why the monocultural system of justice that we have in N.Z. is completely incapable of fairly determining the criminality of any issue of another national culture. In fact the act itself is as native to Aotearoa as the Kauri is, as the system that inevitably ruled it to be criminally offensive and the Oak are native to England.” (p.15)

The book starts with some background. Responding to the Muldoon’s criticism that the Māori protest movement was “being led by pakehas”, using pakeha methods, Mihaka hit upon the idea of using a traditional Māori form of protest. The whakapohane was carefully planned and prepared. Mihaka donned himself in tā moko, then wearing only a piupiu (flax skirt) he performed a haka as the Royal party approached, then turned around and exposed his bum.

Later in court Mihaka presented as evidence a leaflet signed by a coalition of Wellington progressive groups in the form of an open letter to the heir to the British throne. It is worth quoting at length:

After lengthy and serious discussion on the matter, we the undersigned express our strongest and unequivocal objection to your visit to our country. While it is clear you don’t have too much control over such matters, it is equally clear that, as heir to the so-called Commonwealth, and therefore, head of State of N.Z. – whose foremost priority has always been to protect the interests of Big Business – you are a well rewarded, willing, and consequently acquiescent “victim of circumstances”.

With the World Economy as it is, and the irreversible decline of the average New Zealander’s basic standard of living, we consider your expenses-paid tour – to the tune of hundreds of thousands of dollars- to be a gross insult, to any reasonably intelligent person. This is not to say of course, that those who are supposedly full of love and enthusiasm for you – conservative anguine anglomaniacs, unsuspecting school-children, so called responsible Maoris or fervent readers of N.Z. Women’s Weekly – should be deprived of the pleasure of seeing you, your now wedded fiancée or your son. All we say is if they do, then it is a pleasure for which they, who are that way inclined, should be made to carry the burden…

The Treaty of Waitangi of 1840, which a N.Z. Company correspondent at the time considered to be merely be “something to occupy the minds of savages” and is linked to your Tipuna whaea, Queen Victoria’s name, should properly be described as the TREACHERY of Waitangi. For the effect of that event, accelerated the disintegration and dissipation of the Maori people.

This prompted them to resort to various measures to arrest the demise of their nation. One of these was to establish a Native Monarchy…We are as hostile to the national label as we are to the very essence of what constitutes that institution – the Monarchy. That is whether they be skinny or fat, black or white, Maori or Pakeha, male or female.

The only consolation to us (which should not be confused with hope), is the knowledge that history often repeats itself. This immediately brings to mind the sad but perhaps unavoidable fate of your tupuna or ancestor, THE FIRST CHARLIE in Jan of 1649. Then he had seriously misjudged the outrage of (what he thought were his loyal subjects) the people, at their deplorable social conditions, as love and longing for him. He appealed to them to take up arms and help him regain his estates from Parliament, but that proved to be an error he literally paid for with his head.

God rest his soul.

Naturally we hope for better things for you.

In conclusion and citing this occasion as reliable precedent, we will take this opportunity to remind you again, “of all political elements, The People is by far the most dangerous for a King.” (p. 33)

Mihaka was at pains to point out that the protest was not simply a “brown eye” as some newspapers and one police witness had described it. He called as a witness retired Senior Lecturer in Maori Studies at Victoria University William Parker. Parker gave a thorough account as to how the act was culturally sanctioned in Maoritanga. He gave several historical examples, including the case of Dr Maui Pomare’s attempt to enlist Waikato Māori to fight for “King and Country” in the First World War. Pomare was greeted by a large number of Tainui women who treated him to a whakapohane en masse, in order to communicate their unequivocal verdict on conscription.

Mihaka used the platform of the court to deliver a Marxist analysis of how the Monarchy has been a vital prop of class society for centuries. He also detailed the close link between the Crown and imperialism, illustrated by the example of Prince Charles’ speech in Papua New Guinea for the Independence Celebrations in 1975. Charles addressed the people of Bougainville, who had declared their own independence in an attempt to throw off the stranglehold of Rio Tinto Zinc, who were destroying the island with open cast copper mines. Quoting an epistle of Saint Paul he warned:

Everyone must obey the State Authorities for no authority exists without God’s permission and the existing authorities have been put there by God. Whoever opposes the existing authorities opposes what God has ordered and anyone who does so will bring judgement upon himself. (p.80)

Along the way, the authors give plenty of sound practical advice as to how radicals should deal with the legal system. What “Whakapohane” shows is that, if well-thought out, stunts can occasionally be deployed as an effective form of protest.

Forward to a Working People’s Republic!

Where is Don these days???

ps. Great Book, to the bugger that stole my copy! can I please have it back!!!