Mike Walker, PFLP Solidarity Campaign coordinator

The Spark August 2010

On the 20th of September 2001, during a joint session of congress, George Bush uttered the now famous phrase “every nation in every region now has a decision to make. Either you are with us, or you are with the terrorists.” The resulting ‘War on Terror’ is not only being fought on the battle field but also in the minds of people worldwide through a complex web of legislation and International Law. New Zealand is an active participant in the global war against terror being led by the United States in Afghanistan and Iraq. But this should be understood within the context of New Zealand’s long history of repressing its own population.

Maori Resistance

On February 22 1860 the New Zealand government declared martial law stating “active military operations are about to be undertaken by the Queen’s forces against Natives in the Province of Taranaki”. The crime that prompted this declaration was nothing more than unarmed Maori confronting agents of the Crown as they attempted to survey the Pekapeka block at Waitara in Northern Taranaki. The declaration of martial law allowed the Crown to adopt a policy of attrition or “scorched earth” involving the destruction of villages and cultivations. The aim was to reduce the ability of those considered by the Crown to be rebels to make war and hinder European settlement. This was quickly followed up with the New Zealand Settlements Act in 1863. The Preamble stated the North Island has been subject to “insurrections amongst the evil-disposed persons of the Native race”, and was used to further confiscate Maori land. The Act’s stated purpose was “the prevention of future insurrection or rebellion” by Maori and “for the establishment and maintenance of Her Majesty’s authority and of Law and Order throughout the Colony”. This was to be achieved by the “introduction of a sufficient number of settlers able to prote

ct themselves and to preserve the peace of the Country”.

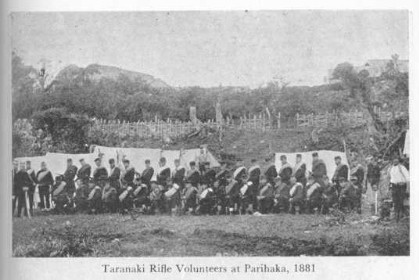

It mattered not to the New Zealand government whether the rebellion was violent or passive, as was shown in Parihaka. Passive resistance campaigns

led to more than 420 ‘ploughmen’ and 216 ‘fencers’ from throughout Taranaki being arrested and imprisoned. Only 40 ‘ploughmen’ received a trial. Special legislation was passed, first to defer the remainder of the trials, and then to dispense with them altogether. On November 5 1881 more than 1,500 Crown troops, led by the Native Minister, invaded and occupied the settlement of Parihaka. No resistance was offered and 1600 residents were expelled. Houses and cultivations in the vicinity were systematically destroyed, and stock was driven away or killed. Maori of Taranaki reported that women were raped and otherwise molested by their attackers. Special legislation was subsequently passed to restrict Maori gatherings and movement and entry into Parihaka was regulated by a pass system. Parihaka leaders Te Whiti and Tohu were charged for sedition and held until 1883. Their trials were postponed and ultimately special legislation was passed to provide for their imprisonment without trial. This legislation also indemnified those who, in the action taken to “preserve the peace”, might have exceeded their legal powers.

Workers’ Resistance

In 1913 the government used force to quell a waterfront strike in Wellington and followed up its “victory in the streets” with legislation to restrict picketing and prevent striking. Richard Hill, in his History of Policing in New Zealand series stated that the government was “determined to destroy its class enemies”, showing more concern for “crushing the water siders” than for “getting the wharves going”. In 1932 spurred on by wage cuts, the government’s treatment of the unemployed and an economic depression, 20,000 workers exploded onto the streets, this time in Auckland. The government blamed a “lawless minority” and “communist agitators” for violent clashes and used the incident as an excuse for the introduction, under urgency, of the Public Safety Conservation Act 1932. The law was described as “potentially the most dangerous and repressive piece of legislation on the New Zealand statute books” at the time. The Act enabled the Governor General to declare a state of National Emergency whenever “the public safety or public order is or is likely to be imperilled.” Once an emergency was declared the executive could issue a declaration on any topic that it considered “essential to the maintenance of public safety and order and the life of the community.” Unlike the 1920 UK statute it was based on, the New Zealand version reserved no protection for the right of workers to strike. On September 20 1950, the National government invoked the Act in response to workers’ militant actions on the water front. Minister of Labour William Sullivan stated that the workers’ rebellion “just cannot go on. No self-respecting government could tolerate it.” The dispute continued and on February 21 1951 a state of emergency was again declared and used to enact sweeping “Waterfront Strike Emergency Regulations”. These prohibited processions, demonstrations, pickets and signs of support of the locked out workers and gave the police extremely wide powers of arrest and entry while essentially censoring the media by prohibiting publication of anything likely to encourage the industrial action. It was also made an offence to provide food or clothing to the locked out Watersiders. On two other occasions the National Government threatened to use the Act, in 1976 against electricity workers and in 1982 against workers at the Marsden Point refinery.

Good vs Evil?

Throughout the 1990s and into the new millennium, New Zealand increasingly participated in a variety of international sanctions programmes initiated by the United Nations against certain ‘rogue’ countries and governments. Post September 11 and the attack on the Twin Towers in New York, the New Zealand government passed a unanimous resolution outlining “New Zealand’s strong resolve to work with all other countries in the international community to stamp out terrorism and swiftly to bring terrorists to justice”, the practical application of which culminated in the Terrorism Suppression Act of 2002. Prime Minister John Key recently designated four organisations as ‘terrorist entities’ in New Zealand, justifying it by stating they engaged in “terrorist acts including the indiscriminate killing of civilians and assassination of political leaders.” This blatant hypocrisy promotes the idea of a dichotomy between good and evil. It discourages critical thought about the real causes of the material circumstances that breed liberation movements across the globe and attempts to delegitimise and suppress support for them. The very same Western regimes that write and enforce international law, and so-called terrorist legislation, are the same regimes hell bent on controlling the resources and wealth of the third world to the detriment of its people.

New Zealand’s ‘enemies’, as dictated to us, will have their violence condemned as terrorism, their legitimacy questioned, their motives vilified and their victims paraded in front of us daily on the news. Conversely our ‘friends’ and ‘allies’ use of violence will be portrayed as necessary, their motives pure, their legitimacy without question and their countless victims faceless.

Just another WordPress site