The first international Rugby superstar with a wider appeal and awareness than rugby fans was Jonah Lomu. While terms such as ‘greatest player ever’ ‘living legend’ etc. can be bandied about easily enough, it is generally agreed that the power and influence of Lomu on the international rugby arena was immense. His sheer power, pace and image shocked and awed the international sporting world. Like with many sportspeople defined as ‘The Greatest’ it is not just the records that carry weight, it is the extraordinary effect of ‘the idea’ of the player on the wider viewing public that lifts someone above the shoulders of their fellow competitors.

The first international Rugby superstar with a wider appeal and awareness than rugby fans was Jonah Lomu. While terms such as ‘greatest player ever’ ‘living legend’ etc. can be bandied about easily enough, it is generally agreed that the power and influence of Lomu on the international rugby arena was immense. His sheer power, pace and image shocked and awed the international sporting world. Like with many sportspeople defined as ‘The Greatest’ it is not just the records that carry weight, it is the extraordinary effect of ‘the idea’ of the player on the wider viewing public that lifts someone above the shoulders of their fellow competitors.

Sonny Bill Williams (or SBW for the many readers, who I’m sure pay little or no attention to organised sport) is the second player following Lomu who most clearly fits the bill of ‘Superstar’. Yet this is a player who has played for the All Blacks rugby team for only two years, failing in his attempt to attain a starting spot in the team to Ma’a Nonu. Boxing aficionado and parasite capitalist Bob Jones has described SBW’s capabilities in his boxing side project as being “He can’t box. …but that’s hardly surprising given his novice status.”[1]. In his most recent fight against 43-year-old gospel singing, sickness beneficiary, Alipate Liava’a, he couldn’t even score a knockout, cue Jones’ negative reaction. However as spectacle SBW is a Superstar. With his boxing match raising over $350,000 for the Christchurch earthquake.[2] Alongside his boxing efforts, his every move is debated and discussed, in a manner far greater and wider than that of either Dan Carter and Richie McCaw, two All Blacks players, generally acknowledged as two of the greatest players to have played Rugby Union in any country in any time.[3][4]

This situation explains most clearly (but somewhat indirectly) Marx’s intention behind the phrase “the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce”[5]

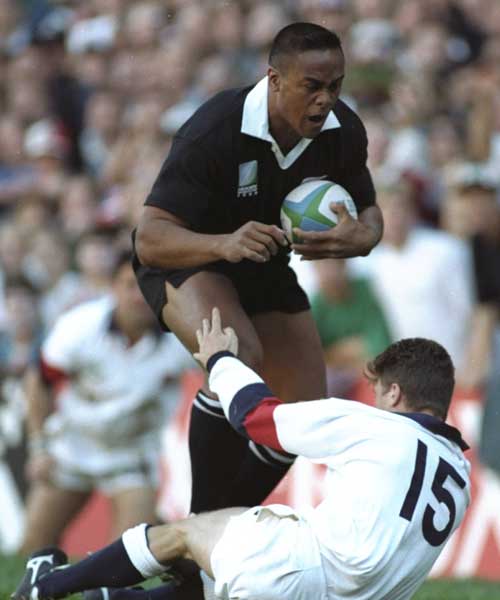

The question then, revolves around the concept of the spectacle and SBW’s place within the spectacle. Within this conception of SBW, meaning becomes more abstract and less obvious than say Jonah Lomu whose initial meaning is more obvious, primarily in the act of scoring tries and particularly in the act of the creation of the monstrous black man using sheer force and power rather guile and deception in the scoring of said tries. Framed around this is the constant go-to within rugby circles of the racist conception of Maori/Polynesian players as not being as intelligent or capable of decision-making as ‘white’ players.[6] The historic image of Jonah Lomu running over Mike Catt contains all these ideas.

The Meaning of Sarkozy by French Philosopher Alain Badiou is a reference for both the title of this column but also an idea of the meaning of SBW himself and what he represents, what he ‘means’ on a wider level. One of the key points put forward by Badiou is the idea that the election of French President Nicholas Sarkozy, on the first part represents the fear of the electorate by electing him and in the second part, fear of that fear in the response of the opposition Socialist Party (the French version of the New Zealand Labour Party) to Sarkozy himself. [7] Comparisons can be made in the reaction of the Labour Party to the Don Brash led National Party.

Although SBW does not fully represent the immediate physical fear that Jonah Lomu represented. He reflects a deeper more abstract fear. Of professionalism, neoliberalism and fuller absorption of popular sport into a more commodified form within capitalism. As opposed to Lomu, who is portrayed as a modern day ‘noble savage’, brutal on the field, but kind and gentle off it. SBW is none of that, since his break with league over the salary cap in place, he has become an international player for hire. His stay within New Zealand rugby has been marked by a lack of collective team focus, his decisions have been made for his sake only. His contracts have been short-term one year contracts, as opposed to the four year contract Richie McCaw signed with the NZRU (New Zealand Rugby Union).

Although SBW does not fully represent the immediate physical fear that Jonah Lomu represented. He reflects a deeper more abstract fear. Of professionalism, neoliberalism and fuller absorption of popular sport into a more commodified form within capitalism. As opposed to Lomu, who is portrayed as a modern day ‘noble savage’, brutal on the field, but kind and gentle off it. SBW is none of that, since his break with league over the salary cap in place, he has become an international player for hire. His stay within New Zealand rugby has been marked by a lack of collective team focus, his decisions have been made for his sake only. His contracts have been short-term one year contracts, as opposed to the four year contract Richie McCaw signed with the NZRU (New Zealand Rugby Union).

In short SBW represents on one level the perennial fear of the loss of talented players to overseas market, but on the deeper secondary level. SBW represents a break with the amateur ethos held so dearly within New Zealand sporting folklore. The unpaid team player, putting team and country before himself. On both aspects SBW is a rejection of both. And he is feared for that.

Joel Cosgrove

Just another WordPress site

Meanwhile, Paul Lewis in the NZ Herald blames poor attendances for the Wellington Phoenix soccer team on their being “boring” in the sense of not having a Superstar of this manner…

Meh, 13,000 people showed up to their most recent game. A bigger problem is them sucking. Plus the Wellington Stadium is atrocious in anything but sunny weather, even then it is pretty uncomfortable in the best of times. Much more comfortable to sit in a pub or at someone’s house with sky (there’s another column, the political economy of Sky).

Second in the league is pretty good for a team that sucks, she said veering totally off topic.

I had a similar sort of feeling about the hostility towards Quade Cooper, though I think Epeli Hau’ofa is a better guide to understanding the reaction to Pacific Island players than any French intellectual:

http://readingthemaps.blogspot.co.nz/2011/10/why-they-hate-quade.html

I don’t know Scott, I took a lot out of your post last year when I read it. But I think we’ve come at the topic from different perspectives. I think Sonny Bill as a ‘post-racial’ player is part of the equation, something I didn’t really delve into.

I think the idea of the fear of the fear is something interesting about New Zealand, by ranting about Sonny Bill, we allow ourselves to rage about something deeper that we don’t really engage with on a day-to-day time, there’s a hegemonic aspect to this that reaifies SBW and allows people to engage with their alienation, with the flawed reality of 21st century NZ, without actually directly engaging with it. That was part of what I was poking at, Jonah was a superstar on and off the field, whereas I don’t see SBW as being a superstar on the field…

I think you’re right about Sonny Bill Williams being a symbol of the corporatisation of the game, Joel – and he probably symbolises this more than Quade Cooper. It’s worth noting that during the early part of his career Jonah Lomu was quite commonly treated to the same criticisms SBW receives nowadays – he was perceived as a bit of a glamour boy, as an individualist rather than a team player, as a chaser after the almighty dollar, and so on. I remember Loosehead Len writing a column to defend him against these charges. After Lomu’s health fell apart, and the public witnessed his sad attempts to continue his career, and realised how much rugby and the All Blacks meant to him, the tide of opinion turned, and he was regarded with sympathy.

Well he did have the country’s loudest car sound system. But he was a Christian (SBW is a Muslim, which has not seemed to be a problem per se), he loved his family (in general, barring the Women’s Weekly articles about friction in regards to his various wives.) and he didn’t go overseas during his prime, he stayed in NZ. I see him as a crossover point between amateurism and professionalism, one foot in each camp. All the things you write about Jonah, SBW has consolidated and deepened.

I see Quade Cooper as more of a nationalist device, kiwi kid gone bad, all that is seen to be worse about Australian culture. Corrupted etc. I don’t follow the Australian sports media, so I’m not down with the detail of the commentators’ perceptions of him, or the general public sympathy (or not). I do know that most Australians don’t care about rugby. Now if he was playing Aussie Rules…

I’m not sure he is feared, I think NZers like him. That photo you chose of him changing his shirt caused a big fuss iirc. I think it has something to do with the sexual fetishisation of Polynesian men in NZ, which nobody writes about but is really pervasive and frankly creepy

The blog about Quade Cooper was spot on though, that’ s a different thing.