Workers Party member Ian Anderson interviews veteran Australian union activist Dave Kieran, on the recently launched Right To Strike Campaign.

The Spark: If you could start with a basic overview of the Right to Strike campaign, and how it started.

The Spark: If you could start with a basic overview of the Right to Strike campaign, and how it started.

DK: The right to strike campaign began about a fortnight ago in its current form, where 6 unions attended a meeting to establish a national campaign, and to work practically towards resolutions in workplaces, up through unions and union executives, approach civil society and civil movements, faith-based communities etc seeking similar resolutions of support.

It’s based very much on the International Labour Organisation (ILO) framework, which indicates that the right to strike actually underpins the will of the people; that is, all of our other rights are protected by the right to strike. Certainly industrially, things like the right to organise, right of entry, are protected by the right to strike.

To establish a bit of history, it was the move in 1977 in Australia against the right to take solidarity strikes that then led to the privatisations, deregulation of the banks, of the labour markets, basically the neoliberal agenda rolled out once the right for workers to show solidarity was made illegal.

The Spark: Why is the right to strike so important politically?

DK: In surprising ways. Given the rollout of the neoliberal agenda globally, there is so much about a representative democratic model that is obsolete. There are so many decisions that communities – regardless of how they vote – call for, that governments do not deliver.

Unions now have an even more important role to play, because if they had the right to strike during the neoliberal reforms, they could have taken action against the privatisations, against deregulation, against redundancies and so on.

The Spark: Has the right to strike ever actually been unrestricted in Australia?

DK: No, never. I don’t know of any country where that is the case. In Australia the right to strike is always something that was taken, and never provided by law.

Unfortunately, what unions did in the ‘70s was to believe that unions could duck and weave the anti-solidarity laws. If you had a dispute in Factory A, and there was a dispute in Factory B, it would be maintained that they actually had nothing to do with each-other. In the end, that meant we could be painted as partaking in fraudulent behaviour. Those of us that were younger leftists back then warned the unions, said “don’t go down that road,” but popular wisdom at the time was that we could duck and weave the laws. But the laws were extended, and we’re more and more corralled.

In so many ways, workers and unions are unequal before the law. It’s illegal for workers to show solidarity with another group because a second employer might be hurt, whereas in an industrial dispute the employer can continue to operate with second, third and fourth employers to their best possible advantage, to achieve an industrial outcome. Employers can employ scabs during a dispute, a secondary labour force – the scab is a secondary partner to achieve an industrial outcome. So we are simply demanding equality before the law.

The Spark: And how do you plan to advance this campaign?

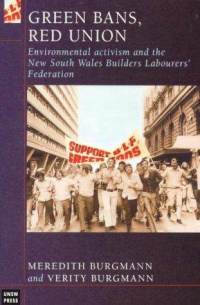

DK: We initially need to build unity in our movement. That initially means the broadest possible discussion and analysis at the workplace level, with resolutions coming through, similar resolutions coming through civil society, through social movements, for example the environment movement – which is always calling for Green Bans to be applied again, but maybe not as cognisant as they could be that the current laws don’t allow for that unlike in the ‘70s. The fact is now that unions can’t even show solidarity with each other, let alone taking action on an environmental claim by the community.

DK: We initially need to build unity in our movement. That initially means the broadest possible discussion and analysis at the workplace level, with resolutions coming through, similar resolutions coming through civil society, through social movements, for example the environment movement – which is always calling for Green Bans to be applied again, but maybe not as cognisant as they could be that the current laws don’t allow for that unlike in the ‘70s. The fact is now that unions can’t even show solidarity with each other, let alone taking action on an environmental claim by the community.

So it’s a matter of building that solidarity infrastructure, so we work towards a day when we pick the appropriate (or inappropriate) employer, and simply announce that we are coming for you. Whilst you are willing to act in such undemocratic and inequitable ways, we are organising to come for you.

But initially we must have the discussion with our communities, because our communities had such a job done on them that they do see strikes as a destructive thing. So it’s the discussion, resolutions, choosing the appropriate target, and then taking strike action.

The Spark: What are the risks of taking strike action?

DK: Well there’s this myth that we have the right to strike – but it’s only within an Enterprise Agreement, and even then it can be called off by a third party. So if you break those constraints, the penalties for unions are enormous.

If they strike with a view to actually close down a workplace or an industry, the unions can be fined hundreds of thousands of dollars a day, workers can be fined hundreds for each day of the strike – whereas an employer can close down an entire workplace or industry, move offshore and there are no penalties.

The Spark: Can you talk about Union Solidarity, and how that is connected.

DK: I should say from the outset that Union Solidarity is gone. It was an attempt by community members to take action where unions could not; so if they wanted to trade with a secondary employer, or employ scabs, then we would hit their secondary employer. We would close them.

It was an organisation that unlike unions had nothing to lose, and would go the whole way. My suspicion under Abbott is that this will be coming from a multitude of directions and organisations.

The Spark: How do you plan to orient to non-unionised workers.

DK: Well, in Australia as in New Zealand, unionisation is around 20% of the workforce and less in the private sector. So you have a lot of people in the service sector who know if they lose, they can lose their job. You can’t guarantee victory without the right to strike.

The Spark: Are you forming any international links?

DK: Yes, one of the features of this is to move through the various international organisations, for example the International Transport Federation, and demand that all laws be framed by the conventions that we’re signatories to. We have to demand that in the first second and third worlds, the right to strike is unrestricted.

Just another WordPress site