The emergence of the Mana Movement has given an urgency to our drive to renew our perspective on Māori liberation. Furthermore, the departure of the Redline group has given us cause to re-examine our past positions on a number of matters, including indigenous issues. In order for us to begin that work, I have tried to reconstruct those former positions. This was far from easy, since most of the early WP material is no longer available on line, and my personal involvement with the Party was fairly marginal when the Foreshore & Seabed controversy broke. The latter, along with the WP position on the Treaty of Waitangi and Tino Rangatiritanga (TR) form the three topics of this discussion document, since those were the major issues of contention between ourselves, the rest of the left, and the Māori Sovereignty movement.

The emergence of the Mana Movement has given an urgency to our drive to renew our perspective on Māori liberation. Furthermore, the departure of the Redline group has given us cause to re-examine our past positions on a number of matters, including indigenous issues. In order for us to begin that work, I have tried to reconstruct those former positions. This was far from easy, since most of the early WP material is no longer available on line, and my personal involvement with the Party was fairly marginal when the Foreshore & Seabed controversy broke. The latter, along with the WP position on the Treaty of Waitangi and Tino Rangatiritanga (TR) form the three topics of this discussion document, since those were the major issues of contention between ourselves, the rest of the left, and the Māori Sovereignty movement.

I want to begin by acknowledging the specificity of Aotearoa, in that it is unique amongst imperialist countries in having a sizeable indigenous population possessing a significant social weight. This fact is important to Cultural Nationalists as well as Marxists: “Unlike any other indigenous colonized people, the Maori live within white culture. Not on reserves. Not in rural areas. […] This is the Maori radicalizing potential.”[Awatere]

The Treaty

The Treaty

We have recently had some debate within the WP around the character of pre-European Māori society. I believe that the basic argument advanced in Ray Nune’s pamphlet is correct – that the lack of a regular surplus in pre-European Māori society prevented the formation of class society.

In any case, Māori did not have any concept of private property in the form of land:

The Maori people […] were not interested in the ownership or “possession” of land as the Treaty expressed it. Philosophically, at least, it was land that possessed the people. Land was a medium for building and maintaining relationships. Buying and selling real estate was unknown. But it was soon to become only too problematic.

In 1835, the British Resident, James Busby convened a meeting of 34 chiefs to sign a Declaration of Independence, designed to head off claims from rival imperialists.

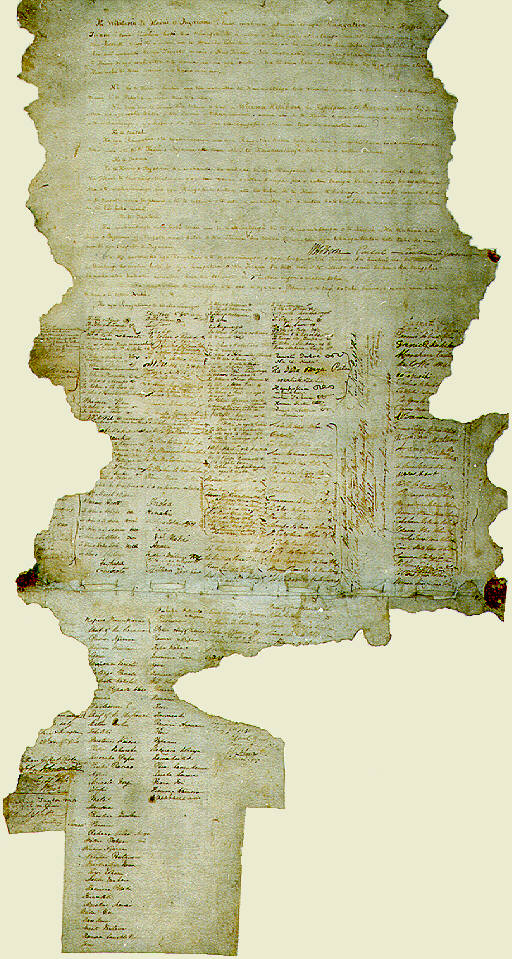

As Europeans continued to arrive in ever greater numbers, Governor Hobson was instructed to obtain the surrender of sovereignty from the chiefs in order to enable annexation. Some chiefs opposed signing. Forty-three Chiefs signed the Treaty of Waitangi on 6 February 1840. Over the following months, many other chiefs signed, bringing the total number of signatories to around 500.

As each chief signed, Hobson shook hands, saying, “He iwi tahi tatou” (We are one people), thereby laying down the ideology of assimilation that was to dominate colonial policy well into the twentieth century. Each chief who signed the Treaty was given two blankets and some tobacco.

The English version of the treaty clearly states (Article 1) that the chiefs cede “Sovereignty” to the Queen of England. The Māori translation, however, renders the word “Kawanatanga” – a transliteration of “governance” which had no equivalence in Māori society. Moreover, Article 2 of the Treaty guaranteed the chiefs “undisturbed possession” of their resources in the English version, translated as “tino rangatiritanga” (absolute chieftainship) in Māori. Thus the version of the Treaty that the chiefs signed did not appear to relinquish sovereignty for Māori. Ranganui Walker argues that while “nominal sovereignty” may have been ceded to the Crown, the chiefs believed they retained “substantive sovereignty” over their lands.

The Treaty was also significant in being the first official document to refer to tangata whenua as “Māori” (literally: normal, usual or ordinary). Pre-European contact Māori had no single term for themselves; groups were distinguished by their tribal names alone.

Extensive efforts were made to secure more signatures of North Island chiefs, but two paramount chiefs refused to sign, Te Wherowhero (Tainui) and Te Heuheu (Tuwharetoa). Te Heueu repudiated those who had signed with the words:

I will not agree to the mana of a strange people being placed over this land. Though every chief in the island consent to it, yet I will not. I will consent neither your act nor your goods. As for these blankets, burn them.

Hobson declared the whole of the South Island, terra nullius (“land belonging to no one”), thus dispensing with the need to obtain the consent of Ngāi Tahu.

At the time of the signing of the Treaty, Māori outnumbered Pākehā ten to one. The chiefs who signed could not have envisaged the consequences of colonisation that was to follow. Ranginui Walker commented that: “By their acquiescence in the Treaty, the chiefs opened the way to replicate among their own people the colonial experience of African tribes and the Indians of the American continent.”

The colonial state almost immediately ignored and neglected the Treaty, but for Māori it was the major point of reference with the state that they returned to again and again. Movements such as the Kingitanga and Kotahitanga appealed to the government by reminding it of its obligations under the Treaty.

Chief Justice Prendergast declared the Treaty to be a “simple nullity” in 1877, but latterly the Crown’s view has shifted significantly. The Fourth Labour Government introduced the Treaty of Waitangi Amendment Act in 1985, which made claims retrospective to 1840, which Walker credits to pressure from the emerging Mana Motuhake. “Consequently, the activist movements suspended resort to direct action, as the tribes moved to avail themselves of the tribunal and other legal avenues”

The balance of power between the Crown and iwi meant that proportion of land returned, and the per capita value of settlements has been very low. “When Sir Robert Mahuta was asked why Waikato settled for so little he replied ‘Because we’re tired of being poor.’”

There are Māori activists who focus exclusively or excessively on the Treaty. Sections of the Mana Movement are not immune from such “Treatyism”. Such an approach is mistaken, not least because it’s not hard to conceive of a thought experiment in which British imperialism annexed New Zealand through military conquest alone, and without resort to the deception of a treaty (as it did elsewhere).Would this scenario mean that Māori could therefore claim no group rights? Clearly such rights need to derive as much from Māori’s status as tangata whenua, as from their enshrinement in the Treaty.

That said, to ignore or downplay the significance of the Treaty (as the WP has done) is ahistorical. We must acknowledge that the Treaty has been, and continues to be, a point of resistance between Māori and the Crown.

That said, to ignore or downplay the significance of the Treaty (as the WP has done) is ahistorical. We must acknowledge that the Treaty has been, and continues to be, a point of resistance between Māori and the Crown.

What I think the WP has failed to grasp is that there are two Treaties. There is the the Treaty, a fraud perpetrated by British imperialism designed to achieve colonisation on the cheap; and Te Tiriti, a contract in which Māori agreed to the settlement of tau iwi, but did not renounce their sovereignty. It is the latter treaty from which TR activists derive their radical subjectivity. Perhaps some of that outlook is utopian and backward-looking, like the hankering for a Saxon golden age by English nationalists who denounced the “Norman yoke” in the 17th century. But I don’t think it is entirely.

The Foreshore and Seabed

In 1997 a confederation of tribes from the northern part of the South Island, Te Tauihu o Nga Waka, applied to the Māori Land Court to determine whether their customary rights to the foreshore and seabed remained extant. The confederation was concerned about the impact of aquaculture on their customary fishing rights, and was frustrated at being shut out of the marine farming industry by Marlborough District Council.

Judge Hingston reached the conclusion from the case that, in the absence of evidence of express extinguishment, customary title to the foreshore remained extant. In 2001 the Attorney-General appealed this ruling. Te Tauihu o Nga Waka appealed to the High Court in 2003. Chief Justice Sian Elias concluded that the Māori Land Court had the jurisdiction to determine the status of the foreshore and seabed. The response of the opposition National Party was to polarise the issue along racial lines, stoking up fears of Pākehā being denied access to the beach.

In January 2004, Don Brash delivered a speech to Orewa Rotary Club denouncing alleged Māori privilege. He asserted that “The Treaty of Waitangi should not be used as the basis for giving greater civil, political or democratic rights to any particular ethnic group.” The reaction of the Labour-led government was to pass the Foreshore and Seabed Act in November 2004, which deemed the title to be held by the Crown.

In January 2004, Don Brash delivered a speech to Orewa Rotary Club denouncing alleged Māori privilege. He asserted that “The Treaty of Waitangi should not be used as the basis for giving greater civil, political or democratic rights to any particular ethnic group.” The reaction of the Labour-led government was to pass the Foreshore and Seabed Act in November 2004, which deemed the title to be held by the Crown.

My recollection of the WP attitude towards the F&S Act at the time was: (i) that it was no big deal, and (ii) that it was probably better for the foreshore to remain in “public” hands, than to be controlled by what may be undemocratic iwi. On the first point, we missed the boat on how important (even if only symbolically) the issue was to Māori. On the second point, reading the Act as being “nationalisation” of the foreshore was way wide of the mark for several reasons.

Firstly, nationalisation is not always progressive. There is perhaps some parallel here with the “orthodox” Trotskyists who accommodated to the the Stalinist states by making a fetish of their “progressive nationalised property”. James Connolly’s comment is apposite on this point:

[S]tate ownership and control is not necessarily Socialism – if it were, then the Army, the Navy, the Police, the Judges, the Gaolers, the Informers, and the Hangmen, all would all be Socialist functionaries, as they are State officials – but the ownership by the State of all the land and materials for labour, combined with the co-operative control by the workers of such land and materials, would be Socialism. […] To the cry of the middle class reformers, “make this or that the property of the government,” we reply, “yes, in proportion as the workers are ready to make the government their property.”

Secondly, there is the historic relationship of land alienation between Māori and the Crown. Often, “it was the state that took their land, not individual settlers.” And finally, there was a racist double standard within the law, in that it extinguished Māori customary rights, but did not expropriate any of the roughly 30% of coastline under private ownership (mostly in the hands of rich Pākehā).

Annette Sykes described the Act as “the largest confiscation of land since the early colonial period.” The WP did not engage with the spontaneous movement of the June 2004 hikoi. It was during this ferment that the Māori Party was launched, as a split from Labour. Pita Sharples set the tone by declaring the party to be “neither left nor right”.

Annette Sykes described the Act as “the largest confiscation of land since the early colonial period.” The WP did not engage with the spontaneous movement of the June 2004 hikoi. It was during this ferment that the Māori Party was launched, as a split from Labour. Pita Sharples set the tone by declaring the party to be “neither left nor right”.

The National-led government repealed the F&S Act as part of its coalition deal with the Māori Party. It was replaced with the Marine and Coastal Area (Takutai Moana) Act 2011 which allowed Māori the right to make claims for protected custody rights, but based on the extraordinarily high threshold of proof showing customary use dating back to 1840. The consequence of these laws today, says Sykes, is that: “the government is licensing transnational companies like Petrobras to mine the petroleum and other mineral deposits which subsist in the continental shelf.”

Tino Rangatiratanga

Tino Rangatiratanga

Donna Awatere’s Maori Sovereignty, based on articles published between 1982-3, is regarded as the sourcebook of the modern TR movement. Awatere advanced the bleak thesis that all white people were captives of their “own” culture, that “white society” could not be changed, and that Māori should instead seek their liberation through “withdrawal and exodus.” Potentially progressive allies were written off as hopelessly conservative (Trade Unions) or mired in splits caused by “individualism” (the Left). Even Pacific Islanders were dismissed as having formed an uneasy alliance with Pākehā against Māori Sovereignty.

Today, parts of the polemic are obviously very dated (such as Awatere’s assertion that there is no New Zealand identity (independent of British colonialism). However, many of the heavily essentialist notions she presents have since become widely accepted, albeit in a watered-down form. There is a radical gloss to the thesis, drawing on Gramsci. She accuses the Trade Union and Left Wing movement of possessing a corporate class consciousness based on “inward looking selfishness”, which she counterposes to the opportunity to create a hegemonic class consciousness based on Māoritanga.

Arguing from a Marxist perspective, Evan Te Ahu Poata-Smith commented:

Awatere’s account of the Pākehā left had such a powerful political impact precisely because it highlighted many of the inherent weaknesses and real shortcomings of the ideas that existed on the left. Unfortunately, however, it often prevented through its very rhetoric and posturing the possibility of building a mass movement that represented a real challenge to racism and the state because its emphasis on autonomy in struggle resulted theoretically at least, in the exclusion of Pākehā, whatever their social class and gender, from playing a key role in fighting for Māori liberation.

Ranganui Walker has written a historical account of the struggle for Māori liberation from the perspective of cultural nationalism. Attempting to explain recurring divisions within Māori movements, Walker states that: “ Although Maori radicals are the cutting edge of social change, the conservatives are the slow grinding edge.” Poata-Smith, however describes how class interests can actually lead to a contradiction of interests of the two. For instance, he describes how conservative elements within the Ngāti Whātua leadership eventually colluded with the government to end the occupation of Takaparawhau/ Bastion Point, “reveal[ing] that on the one hand the Maori middle class will support certain kinds of struggle so long as it advances their interests but their endorsement of militancy is sharply curtailed if the protest actions threaten their own position or the system itself.”

Poata-Smith further notes how the frequent denunciation of such leaders as “sell out”, “kupapa”(traitor), or “house nigger” by radicals, fails to explain their social role. Far from lacking cultural fortitude, “this group of Māori are perfectly conscious of their own interests. The problem is, however, that their material interests are not the same as those for working class Māori.”

Poata-Smith identifies how the interpretation of TR has been transformed a number of times:

In the period from the early 1970s onwards, four interconnected interpretations were to emerge: tino rangatiratanga as Maori capitalism (in tribal or individual form), tino rangatiratanga as Maori electoral power (primarily through the orthodox parliamentary system), tino rangatiratanga as cultural nationalism, and tino rangatiratanga as involving more radical far-reaching strategies for change.

The degeneration of elements of the TR movement has been latterly analysed by Sykes, who identified her own previous complicity with “the rise of a Maori elite with the process of litigating, negotiating and then implementing Treaty settlements, many of whom have become active sycophants of the broader neo liberal agenda which transfers a limited subset of publicly owned assets and resources into the private ownership of corporations to settle the injustices that have been inflicted upon hapu and iwi Maori.”

Along with the rise of the corporate warriors, Poata-Smith also identifies collapse of Stalinism as politically disarming groups such as the CPNZ and SUP, who were unable to effectively oppose the generalised retreat from class and socialism.

Sykes, whose background is in leftwing cultural nationalism, has to a large extent converged with the Marxist analysis of the trajectory of the TR movement. But idea of the Ao Māori/ Ao Pākehā world view is still widely accepted within Mana. Poata-Smith contends, “Given that identities are blurred, multiple and historically contingent the idea that the main division in society is between Māori and Pākehā also risks fragmentation of the movement itself because it inevitably leads to confusion and fights over authenticity.”

Sykes, whose background is in leftwing cultural nationalism, has to a large extent converged with the Marxist analysis of the trajectory of the TR movement. But idea of the Ao Māori/ Ao Pākehā world view is still widely accepted within Mana. Poata-Smith contends, “Given that identities are blurred, multiple and historically contingent the idea that the main division in society is between Māori and Pākehā also risks fragmentation of the movement itself because it inevitably leads to confusion and fights over authenticity.”

Elizabeth Rata’s take on TR is worth examining, especially since Phil Ferguson claimed that she was an academic whose views were close to that of the WP’s. Rata argues stridently against the constitutional inclusion of any “foundational group rights”. She charts the emergence of an elite based on the creation of what she calls “neo-tribes” (to distinguish them from traditional iwi). This is based on a “total rupture” between the pre- and post-colonial periods, due to the traditional redistributive Māori economy being incompatible with accumulative capitalism. Ideologies of culture like neo-traditionalism (emphasising kin over class) and culturalism (identity is primary) support the new elite.

To this phenomenon, she counterposes the political economy approach, where politics and economics are primary (but “textured” by culture). The group rights alternative, Rata argues, leads to brokerage politics and the formation of a self-interested elite.

I think Rata provides a trenchant critique of the “Brown Table” with her analysis. However, she conflates that tendency with the whole of the TR movement. She ignores the class struggles occurring within iwi and hapū. And her motivation for opposing group rights is that: “The structural cohesion of the nation-state itself will be destabilised by altering the meaning and practice of citizenship.” Well, we want to smash the state!

Rata also overemphasises the historical rupture of colonisation. Whist most Māori today may be urbanised, proletarianised and detribalised, many still retain strong links to their “bones”, their ancestral lands and traditions. The victory of capitalism is not as complete as Rata makes out.

To Poata-Smith’s list, we may add a fifth interpretation of TR: self-determination in legal processes. Moana Jackson writes of the “criminality of imposed law” of colonisation and repudiates the idea that “in Aotearoa Maori people were held to have no law, and therefore no authority, because the early settlers could not discern in Maori society the things they identified as ‘legal’ – the courts, the police, the written reports.” Traditional society had to be suppressed “in order that the monist idea of ‘one [English] law for all’ could be imposed

To Poata-Smith’s list, we may add a fifth interpretation of TR: self-determination in legal processes. Moana Jackson writes of the “criminality of imposed law” of colonisation and repudiates the idea that “in Aotearoa Maori people were held to have no law, and therefore no authority, because the early settlers could not discern in Maori society the things they identified as ‘legal’ – the courts, the police, the written reports.” Traditional society had to be suppressed “in order that the monist idea of ‘one [English] law for all’ could be imposed

Jackson exposes criminal law as largely ideological, and contrary to the liberal view, is subject to political power and cultural bias. Interestingly, Rua Kennena flew a flag with the slogan “Kotahi Te Ture/ Mo Nga Iwi E Rua/ Maungapohatu” (One Law/ For Both Peoples/ Maungapohatu), which was seized as evidence for his trial for sedition in 1916. Today the phrase “one law for all” is used by the likes of Don Brash demagogically and hypocritically (since in reality, Brash supports class law, not “one law”). “The key in the phrase ‘one law for all’”, writes Jackson, “is not the process but the result at the end, and the result must be justice for all.

What I find problematic in Jackson are not his alternatives to the current legal system (a focus on rehabilitation/ restorative justice and community – rather than just individual – responsibility), but rather, his slippage into relativism: “The French have their way of getting justice, the Americans have their way of getting justice, so the Maori people have their way of getting justice, and that is as valid as any other.” My concern is that this approach may inadvertently open the door to reactionary measures, like the introduction of sharia courts to try muslims.

As this brief survey shows, TR is a heavily contested term, and to reject it wholesale seems to me dogmatic and class reductionist. Perhaps we can say, as Socialist Aotearoa do, that TR is impossible to realise without overthrowing capitalism. In any case, it is the task of socialists in the Mana Movement to help redefine and transform TR into a revolutionary cause.

Mike Kay

October 2011

Sources

Awatere, D. (1984) Maori Sovereignty, Broadsheet

Connolly, J. (1899) http://www.marxists.org/archive/connolly/1901/evangel/stmonsoc.htm

Jackson, M. (1991) “Maori Access to Justice” Race Gender and Class

Jackson, M. (1995) “Justice and political power: Reasserting Maori legal processes” in Hazlehurst, K.M. (ed.) Legal pluralism and the colonial legacy: indigenous experiences of justice in Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, Avebury

Kawharu, I.H. (2001) http://www.aucklandmuseum.com/site_resources/library/Maori_Culture/Events_Lectures/Land_and_Identity_lecture_notes.pdf

Kay, M. http://workersparty.org.nz/2010/09/15/book-review-encircled-lands-te-urewera-1820-–-1921-by-judith-binney-bridget-williams-books-2009/

Nunes, R. (1999) http://fightback.zoob.net/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/the-maori-in-prehistory-and-today2.pdf

Rata, E. (2005) http://tazi.net/JFriedman/IMG/pdf/RataSS_20Address12Feb05.pdf

Rata, E. (2011) http://www.nzcpr.com/guest232.htm

Sykes, A. http://news.tangatawhenua.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/Annette_Sykes_Lecture_2010.pdf

Poata-Smith, E.S. Te Ahu(2001) The Political Economy of Maori Protest Politics 1968-1995 PhD Thesis, University of Otago

Poata-Smith, E.S. Te Ahu (2005) http://www.pjreview.info/issues/docs/11_1/pjr11105review_strugg_p211-217.pdf

Walker, R. (2004) Ka Whawhai Tonu Matou: Struggle Without End, Penguin

Pretty good article. I’m encouraged a reference to james connolly was included. As we do not want to replace red coats with brown.

This may be of interest on this subject as it deals with these questions as they arose in the early 1980s.

http://redrave.blogspot.co.nz/2012/01/30-years-ago-owen-gager-on-towards.html

I would add to this reference another draft article from the 90s that covers the same ground. ‘Antipodean Marxism meets Indigenous peoples’ Struggles’.

http://bit.ly/wVbnqz

I’m not suggesting members of the Workers Party should be disrespectful to Ray Nunes as a person, because he was a long-serving and obviously sincere leftie and trade unionist, but they really should quietly consign the treatise he wrote about the ‘secret prehistory of the Maori’ to the dustbin of history, because it’s something of an embarrassment.

Nunes’ understanding of anthropology comes from the Stalin-era Soviet Union. Under Stalin, Soviet anthropologists and ethnologists were forced to work within the confines of the categories that Engels used to describe prehistory in his book The Origin of Family, Private Property and the State. Even in the last years of the nineteenth century, Engels’ book, which was based on a simplification of Marx’s Ethnological Notebooks and his other late researches into pre-capitalist societies, was badly out of date. Engels believed that the American scholar Lewis Morgan had discovered, during his researches into American Indian society, a series of stages through which prehistoric human societies typically passed. Morgan associated these stages with various forms of social organisation and with various technologies. Engels also used Morgan’s work to suggest that the earliest human societies lacked class distinctions. After he took cotnrol of the Soviet Union Stalin integrated Engels’ notion of a series of stages of prehistory into his stagist vision of historical societies, which had feudalism being replaced inevitably by capitalism and capitalism being replaced inevitably by socialism. History became a series of hoops that every society had to jump through.

By at least the early twentieth century, though, anthropologists were using new techniques like scientific archaeology and field interviews to gather evidence that showed that human societes were much more diverse than Morgan and Engels had imagined, and couldn’t be consigned to a series of tidy categories. It was clear that class distinctions did exist in many subsistence societies, and that there were even hierarchies in some hunter gatherer societies. It was also clear that societies evolved in many different ways, and that different modes of production could co-exist in the same prehistoric society. Stalin prevented Soviet anthropologists from innovating in response to this new knowledge, but in Western countries like France Marxist anthropologists reacted to the new data by abandoning the categories that Engels had laid out and instead adapting the method used in Capital to the study of pre-capitalist societies. In his book Marxism and Anthropology Marc Bloch gives an excellent account of the work of these scholars, who laid the basis for twenty-first century historical materialist anthropology…

Ray Nunes’ little book tells us very little about pre-contact Maori society, because Nunes simply can’t accomodate any of the data which anthropologists have collected over the past hundred or so years to the dogmas he has taken over from Stalin and Engels. Nunes’ complete lack of understanding of modern anthropology is shown when he argues that the only relevant material to a study of pre-contact Maori society is the texts of early visitors to this country like Cook. He doesn’t seem aware of the way that scientific archaeology and oral history can provide mountains of data which can complement or contradict the very limited and very Eurocentric material provided by the likes of Cook.

Nunes repeatedly attacks Raymond Firth, who wrote some of the first serious studies of Maori economics, for being an anti-Marxist. In reality Firth had great respect for Marx, and wrote a long essay about the importance of Marx’s work to anthropologists. Nunes accuses Firth of being an anti-Marxist because he argues that the hapu was an important economic unit in Maori society, and because he talks about economic divisions within tribes. But in talking about the role of the hapu within iwi and in acknowledging the hierachical nature of iwi, with their distinctions between chiefs and commoners, not to mention slaves, Firth was simply following the evidence which other scholars had amassed. Nunes can’t admit this evidence exists because he thinks that he has to uphold Engels’ argument that ‘primitive’ societies were egalitarian and didn’t feature anything resembling the modern nuclear family. He rejects all the evidence in order to hold onto this outdated dogma.

As I mentioned earlier, modern Marxist anthropologists dealt with the problem Nunes faced by ditching Morgan and Engels’ schema. For them, it was no problem to admit that class or proto-class divisions existed in ‘primitive’ societies, to acknowledge that different modes of production existed in prehistoric societies, and to accept that different societies could develop in different ways.

Because he’s determined to hold on to the schemas of Engels and Morgan, Nunes makes one outlandish statement after another about Maori and Polynesian society. For instance, he claims that the very low level of Maori social and economic development is shown by the fact that their society never featured pottery. For Nunes, as for Engels and Morgan, pottery is one of the magic signs that supposedly marks out a society as more advanced than others. As anyone who has studied the prehistory of Polynesia knows, though, pottery tended to be a feature of very early, and relatively socially simple Polynesian societies, and not a feature of later, and much more complex societies. The Lapita people, who were the ancestors of the Polynesians, left examples of their beautiful ceramics along the coasts of Tonga and Samoa. The Lapita had a simple economy which leaned heavily on fishing, and featured only a relatively limited amount of agriculture. Their Tongan descendants created, over the course of a couple of thousands years, an incredibly compex society, which resembled in many ways the feudal societies of medieval Europe (when Cook arrived in Tonga he was amazed by the sophisticaton of the farming-based economy, and made comparisons to the Netherlands). But even as Tonga was growing in social sophistication, the art of pottery was dying out. The case of Tonga makes a mockery of Morgan and Engels and Nunes’ claim that pottery is a defining feature of how socially sophisticated a society. Nunes proves nothing at all, then, when he notes that Maori did not have ceramics.

Those preceding comments might seem rather long-winded, but I do think that the nature of pre-contact Maori society is more important than it might at first appear to contemporary left-wing politics in New Zealand. It’s good to see the Workers Party taking another look at its position on Tino Rangatiratanga and related matters, like the seabed and foreshore controversy, but I do think that it’s important also to get up to speed with research and debates about Polynesian and Maori history and prehistory.

If we see pre-contact Maori and Polynesian societies as simple, internally undifferentiated, static, and incapable of internal evolution, instead of dynamic, internally divided, and capable of adapting to new circumstances, then we end up replicating the viewpoint of the nineteenth century colonisers of Aotearoa and the Pacific.

Dave posted a link to a text written by Owen Gager in the early 1980s called Towards a Socialist Polynesia. Gager’s essay is marred by frequent excessively sectarian attacks on various far left groups, but it does make some very good points about the danger of the sort of stagist approach to history and prehistory that Ray Nunes promotes. To his great credit, Gager also shows that Maori weren’t simply swamped by capitalism and modernity in the nineteenth century, but rather created their own economic system and their own version of modernity. To understand the achievement of societies like the Waikato Kingdom and Parihaka, and the potential of contemporary movements like Mana, we have to understand the qualities of pre-contact Maori and Polynesian society.

I used Gager’s polemic as a reference point in an argument with Chris Trotter about his opposition to Maori nationalism:

http://readingthemaps.blogspot.co.nz/2010/04/history-necessity-and-new-zealand-wars.html

Patrick Vinton Kirch is well worth checking out as an antidote to the notion that pre-contact Polynesia was socially undifferentiated, primitive, and static. Working in the synoptic, materialist tradition of the French Annales school and of French Marxist anthropologists like Godelier, Kirch has created a series of portraits of the development of Polynesia which focus on technological change and social division. In his classic 1980s text The Evolution of the Polynesian Chiefdoms, Kirch compares the histories of all of the major Polynesian societies, including Aotearoa. Trashing the patronising idea that all Polynesian societies were socially similar, he shows that Tonga, Hawa’ii and Tahiti had developed into highly stratified, economically advanced places by the seventeenth centuries, in contrast to islands like the Chathams and Pukapuka, where something resembling ‘primitive communism’ reigned. Kirch advances a series of materialist explanations, including ecology, population pressure, and social conflict, to explain the development of stratification.

Kirch argues that Aotearoa was less stratified than Tonga, Hawa’ii or Tahiti, but claims that, except in the south of Te Wai Pounamu, significant divisions still existed between chiefs and commoners (Kirch presents the south of the South Island as an egalitarian society, but other scholars like Atholl Anderson have argued that it was in fact a highly hierarchical place, despite the fact that it had a hunter gatherer economy). Essentially Kirch is arguing that there were two modes of production operating alongside each other in most of Aotearoa: a domestic subsistence mode, which was centred on the hapu, and a chiefly tributary mode, which relied on the communal labour of many hapu – on communally planted gardens, for example – and on tribute from hapu. The fluidity of pre-contact Maori society, where iwi would go in and out of existence, and both iwi and hapu would clash militarily, has been noted by many scholars, and this fluidity, which contrasts greatly with the stability of Tongan or Hawaiian society, probably has a lot to do with the fact that two partly contradictory modes of production existed side by side.

In his more recent books Kirch has developed some of the ideas in The Evolution of the Polynesian Chiefdoms. In The Road of the Winds: an archaeological history of the Pacific Islands he extends his analyses to Melanesian and Micronesian societies, and in The Wet and the Dry he focuses it on Futuna, a small island which has traditionally been home to two very differently organised societies.

I think the original Workers’ Party position had some merit, and it helped me writing my book on the Aborigines’ Protection Society (Hurst/Columbia University Press, 2011). http://www.fishpond.co.nz/Books/Aborigines-Protection-Society-James-Heartfield/9780231702362?cf=3

There I look at the Treaty more as it pertained to the attempted reform of the British Empire coming out of the Select Committee on Aboriginal Peoples of 1837.

The ‘humanitarian’ goal of ‘protecting’ Maoris was not as atypical as it at first appears. Similar edicts were introduced into instructions to the governors of the Australian colonies where there was no treat signed. New Zealand governors (Grey in particular) could draw on their assigned role as protector of Maori interests to rise in a Bonapartist way above the sectional interests of different groups of settlers. This was as much to do with controlling settlers as it was to do with controlling natives.

Politically, I am sceptical about the possibility of deriving a radical impulse from 1840. The Treaty essentially enshrines the rights of the Crown over the Colony, in the name of the Maori.

But then, as the article points out, are we talking about the Treaty (a colonial document) or te Tiriti (from which tino activists derive their radical subjectivity.)

The WP isn’t about to renounce republicanism anytime soon, but we have to engage more meaningfully – Phil’s line says the majority of Maori have no interest (material or subjective) in tino, when thousands were mobilised against the F&S confiscation.

Yes, I think I understand the point, but it seems a bit forced to me – the ‘good treaty’ and the ‘bad treaty’. If there are two interpretations of a Treaty, then there isn’t really a Treaty, is there? If you forgive me I will avoid the specific questions of the recent legal wrangles, which I don’t know enough about (other than to say that thousands have been mobilised against their interests before). On the history, though, it seems clear enough that the Treaty was the expression of imperial policy, and one that was adopted, in different ways, across the Empire.

@James: difference between the two translations is actually a major part of tino politics. While I’m not big on international law, it’s often pointed out that the indigenous translation should be the recognised one.

I think the signing of the TOW offers a good example of the way that a misunderstanding of pre-contact Maori society can lead us astray when we analyse post-contact events. Right-wing politicians commonly argue that when Maori signed the Treaty they relinquished their national independence and accepted British sovereignty; liberal politicians claim that the Maori who signed the Treaty wanted to make a partnership between a Maori nation and the British sovereign. Historians tend to agree with neither claim.

The reality is that neither a Maori nation nor British sovereignty existed here in 1840. As Matthew Wright shows in his excellent new book Guns and Utu, iwi were not only often at war with each but internally fragmented in the 1830s, and British authority did not even exist in the Bay of Islands, where the missionaries and political representatives of the empire were the guests of Nga Puhi. Maori had interacted with small numbers of Pakeha for generations, and no idea that large numbers of Pakeha might soon descend on their rohe, and by turning up and taking land prompt the emergence of a sense of Maori nationhood, and nationalist organisations like the Kingitanga.

The Maori who signed the Treaty were not looking far into the future and making constitutional arrangements – they were pursuing short-term political and economic ends as they struggled with other Maori. Nga Puhi leaders, for instance, wanted the Treaty to cement their status as the most powerful iwi, by making sure that the Bay of Islands remained the locus for trade with Europeans. They were struggling to hold on to the advantages that Hongi Hika had gained with his new-fangled muskets in the 1820s, and trying to prevent the emergence of other areas of New Zealand as ‘hot spots’ for trade with Europeans. On the other hand, some Ngati Kahungungu leaders insisted on signing the Treaty because they thought it would shift the balance of power away from the north. But within iwi like Nga Puhi and Ngati Kahungungu there were dissident groups. Hongi Hika was eventually killed not by one of the members of the many southern iwi he attacked, but by a dissident hapu of Nga Puhi who lived on Whangaroa Harbour, and who had refused to let him dictate their terms of trade with visiting European ships.

But we can only recognise the historical reality of the Treaty if we jettison the idea, which was popular for a time with colonial ethnologists and which was so unfortunately promoted by Ray Nunes, that pre-contact Maori society was not marked by stratification, social conflict and change. To understand the dynamism and conflict which was the backdrop to the signing of the Treaty we have to be able to appreciate that pre-contact Maori societies were dynamic and full of internal conflicts.

Cheers for your contributions, definitely more engagement with pre-colonisation Polynesian history is necessary.

But I don’t think Engels/Nunes anthropology should be taken to mean early societies lack are static and unchanging, unless you reduce dialectics to something solely useful to describe political conflicts in class society – which I find reductionist.

“The Maori who signed the Treaty were not looking far into the future and making constitutional arrangements – they were pursuing short-term political and economic ends”

I agree. But I would like to redirect your interest to the other question, why did the Crown seek a treaty? As well as looking at the motives on the Maori side, we ought ot understand the motives on the British side. After all, the treaty, ultimately, is an instrument of British rule. And while you are right to say that there was no British sovereignty in the 1840s – there was by the 1870s, and its initial basis (later dismissed as a ‘nullity’) was the Treaty. That’s what the Treaty is. It is the founding document of British rule, and the Maori agreeement is essentially a fiction of the Treaty.

That Maori subsequently organised around its claims is another matter.

Hi Ian,

it’s not simply that I disagree with the Engels-Nunes schema – it’s that I don’t see how anybody would be able today to do the most basic research on Polynesian society, or indeed any society, using the schema.

In terms of how completely at odds it is with the facts discovered by anthropologists and people in related disciplines, I’d compare the Engels-Nunes schema to the Celtic New Zealand theory promoted by the likes of Martin Doutre and Kerry Bolton. (I’d add the proviso, of course, that where Doutre and Bolton are raving racists with an anti-Maori agenda, Nunes was a sincere leftie who was running down a Stalinist blind alley).

I don’t have it in front of me, but as far as I remember Nunes’ booklet claims that Maori society existed at ‘the Upper Stage of Savagery’, which puts it, in Engels’ schema, just below the ‘Lower Stage of Barbarism’, which according to Fred ‘dates from the invention of pottery’.

Alas for Ray Nunes, Engels’ schema didn’t admit that societies could practice slavery or the patrilineal inheritance of property and power until they reached the Upper Stages of Barbarism.

I’m sure you’d agree that there’s a mountain evidence which shows that slavery, along with many other features of social stratification, existed in Maori society. There’s also abundant evidence of the passing on of property and power from chiefs to their male offspring.

But Ray Nunes was forced to deny all of this evidence, because it conflicted with the dogmatic schema he had taken from Engels. He felt he had to say that Maori society occupied the ‘Upper Stage of Savagery’, because it didn’t have pottery, but by slotting Maori society into his pigeonhole he had to deny some very obvious features of that society, like slavery and patrilineal inheritance.

These absurd contortions were combined with a conspiracy theory about the work of legitimate anthropologists. Nunes repeatedly accused Raymond Firth and other scholars of being trying to defend capitalism by inventing evidence for theories which conflict with Engels’ schema. I’m reminded of Martin Doutre’s claim that ‘anti-white’ anthropologists and archaeologists are covering up all the ‘evidence’ for his theory that Celts got to these islands before Maori. Both Nunes and Doutre are forced to deny or denigrate the research of serious scholars because they are wedded to a dogmatic and fantastic theory.

Does anyone in the Workers Party really want to take up categories like ‘the Upper Stage of Savagery’ and use them to try to discuss Maori society? I’d suggest we ought to leave that stuff in the dustbin of history.

Disagreeing specifically with the assertion that a classless society necessarily lacks dynamism. Still taking in the rest.

Hi Scott, thank you for your thought provoking comments, I’ll admit that I am not well versed in anthropology! When we last republished Nune’s pamphlet, we included a “health warning” introduction about the Stalinism, etc. On Morgan’s stages, we stated:

Nunes draws on the work, and uses the terminology, of pioneering 19th century anthropologist Lewis Morgan. Morgan in his groundbreaking work developed a theory of stages of society. The terms are largely out of use these days and have pejorative connotations that were imposed after Morgan’s time. While the categories have new names Morgan’s stages are still valid.

John Bellamy Foster, in “Marx’s Ecology” states: “The stages theory that Morgan described are still generally employed in anthropology, although the names have been changed, reflecting the negative connotations associated with the terms ‘savagery’and ‘barbarism.’Morgan’s ‘savagery’is now generally referred to as gathering (with marginal hunting) society – a form of subsistence that obtained throughout the Paleolithic period. Instead of ‘barbarism,’today, reference is made to societies practicing horticulture. Domestication of plants is usually associated with the Neolithic revolution around ten thousand years ago.” (p.216)

Are you saying that Bellamy Foster is wrong about modern anthropology’s attitude towards the stages?

I don’t intend spending a lot of time debating on this website as I prefer to spend time writing for Redline. But as Ray Nunes is not around I’d like to make a few points.

As I recall it, what he set out to do in the letter which forms the basis of the pamphlet on Maori prehistory was to argue how political (and pro imperialist) the field of anthropology was, particularly in the Cold War period, and to address the question of whether Maori society was a class divided society.

Ray was definitely “old school” when it came to Marx and Lenin, greatly respecting their enormous intellects and their scholarly contributions.

Ray thought Morgan deserved recognition for his groundbreaking work and he respected the fact that Morgan undertook decades of very meticulous research. He did, after all, live with the Iroquois for 25 years.

Ray’s view was that Morgan’s stages were the most important, but not the only categories. As I pointed out in the intro to the pamphlet “the terms are largely out of use these days and have pejorative connotations that were imposed after Morgan’s time. While the categories have new names Morgan’s stages are still valid.”

And this view is shared by other Marxists like John Bellamy Foster, which Mike Kay has quoted above.

The key thing Ray takes up in regard to Firth is that his standpoint is that the spiritual and intellectual aspects of Maori social life and custom are primary. Ray is arguing for a examination of the actual mode of production.

Scott arrogantly assumes that Ray didn’t know or take account of the existence of Lapita pottery. Of course Ray knew about Lapita pottery which was long out of production before the first Polynesians arrived in NZ. There are many examples of the decline of technology in history and pre-history which Ray was well aware of. Ray’s point was that without a surplus there couldn’t be a *class* of slaves. The sporadic existence of individual slaves did not constitute a class or a social system. Furthermore, the children of slaves were inducted into the tribe – hardly a sign of a slave society. And, that without domesticable animals, pottery and access to iron ore for making weapons and tools, the productive forces in a society remain stone age.

Scott talks about property in Maori society, but there really was nothing of significance that was treated as property. The main economic resource was land, and I don’t think even Scott would claim that was property.

Scott also claims that modern anthropologists (not the fuddy-duddy traditional Marxist types) no longer view hunter gatherer societies as egalitarian.

In fact Ray was well acquainted with current anthropological texts (up to his death in 1999).

Maybe it is Scott who needs to get a bit more up to date. Chris Stringer, Britain’s foremost anthropologist in his Origin of Our Species, published in 2011, argues that egalitarianism is what differentiates most human hunter-gatherer groups both from our primate relatives and from agricultural, pastoralist and modern industrialized societies. (p 113).

As I’ve said a couple of times, I’m not trying to have a crack at Ray Nunes the man. He was obviously a sincere and dedicated leftist and he meant well when he wrote his booklet on the Maori, just as he meant well when he wrote his equally problematic booklet on Stalin.

Contrary to what Daphna says, though, there is no sign at all that Nunes knew anything about the development of anthropology as a professional discipline in this country, or that he was aware of any of the work of post-Stalinist Marxist anthropologists in the decades since the 1950s.

The fact that Nunes argues that the texts of Cook and other early visitors are the main materials for the study of pre-contact Maori, and never discusses the vast new horizons opened up, in the era of scientific anthropology, by archaeology and by oral historical research, give an idea of his familiarity with the state of the field. The fact that he chooses to make his quixotic attack on Raymond Firth, a very early contributor to the literature about Maori economics and social organisation, and not one of the scores of scholars who have taken Firth’s work forward, amending and updating it, is also revealing.

Nor is there anything in Nunes’ pamphlet about the great wave of creative work done by Marxist anthropologists after the shadow of Stalinism had been lifted somewhat in the 1950s and ’60s. There’s no reference to Godelier, who did so much to create modern Marxist anthropology, no reference to Maurice Bloch, and a bizarre attempt to convict Raymond Firth of anti-Marxism, when Firth was actually responsible for introducing many of his students to Marx’s texts. There’s no acknowledgment at all of Patrick Vinton Kirch’s magnificent historical materialist accounts of Polynesian history, which were being published to huge controversy and acclaim at the time Nunes was publishing his booklet. There’s no reference to John McRae’s explicitly Marxist work on Maori economics at the Universty of Auckland in the 1970s, or Dave Bedggood’s use of modern Marxist anthropology in some of his texts of the 1970s, or Roger Neich’s materialist ethnology, which used the likes of Althusser to think through the meaning of Maori meeting houses. Nunes was out of the loop.

Daphna’s attempt to defend Nunes’ definition of Maori society as part of the ‘Upper Stage of Savagery’ indicates that she doesn’t really understand the problems with his booklet. She claims that the disappearance of Lapita pottery was part of ‘technological decline’ in Polynesia. The opposite is true: the early Lapita colonies in places like Tonga and Samoa were relatively socially and technologically simple fishing communities, and they developed, over millenia, into much more sophisticated societies. Tonga, as I noted before, was a de facto feudal society with an amazingly complex system of agriculture when Cook arrived. The idea that Tonga became less technologically developed in the post-Lapita era is laughable. What happened is simply that the Tongans found it easier to make their plates from wood than from ceramics! The case of Lapita and Tonga shows the absurdity of Engels’ attempt to make pottery into a sort of doorway which a society has to pass as it becomes more advanced.

Daphna claims that Raymond Firth was an idealist who prioritised the spiritual over the material when making explanations of social structures and social change. In fact, Firth was a functionalist, who helped to develop the technique of explaining culture in terms of how it helped to cohere a society and its production process.

Daphna’s claims about the ‘sporadic’ existence of ‘individual’ slaves runs counter to massive evidence for slavery as an institutionalised part of Maori life. Even the accounts of Cook and his crew, which are some of the few sources Nunes seems to have read before he wrote his booklet, make the prevalence of slavery clear. Slaves were taken from other iwi in raids and put to work on large-scale agricultural projects to help generate a surplus. It is by no means true that all the children of slaves were always inducted into iwi.

Daphna’s claim that there ‘was nothing of significance treated as property’ in pre-contact Maori society is contradicted by a vast body of oral history, which talks of struggles between whanau and hapu over all manner of objects, including land and slaves and taonga, as well as the archaeological record, which shows that chiefs, unlike commoners, were commonly buried with valuable pieces of private property.

Daphna goes on to claim that hunter gatherer societies were all egalitarian. This notion is still popular in the West, particularly in green and New Age circles enamoured with cliches of the ‘noble savage’, but the fact is that hunter gatherer societies differ greatly in social structure. Some, like the pre-contact Moriori society on the Chathams, were undoubtedly very egalitarian; others, like the Kai Tahu and Ngati Mamoe societies in the south of the South Island, were most definitely not, as scholars like Atholl Anderson have shown. The point is that one hundred years of research have shown us that societies can’t be pigeonholed into the tidy categories and ‘stages’ of development that Engels laid out. Human society is far more diverse than that.

Hi Mike,

sorry to clog up your comments thread with all this stuff!

John Bellamy Foster is certainly wrong if he’s suggesting that Engels’ and Morgan’s stages have much influence over contemporary anthropology. Morgan is seen very much as an historical figure, and even the vast majority of Marxist anthropologists would reject Engels’ stages. I note that Bellamy Foster isn’t an anthropologist himself – maybe he didn’t research that statement about the influence of the stages before making his statement.

(I’m not an anthropologist myself, by the way, I’ve just been getting into the subject over the past few years, with the help of anthropologist friends. I got interested in the misrepresentation of Maori history when I was working at Auckland museum and realised that loads of people fell for the ‘Moriori myth’ or the Celtic NZ myth – that’s when I started working with a small and informal group of anthropologists and other eggheads to try to counter some of the pseudo-scholarship – cf http://readingthemaps.blogspot.co.nz/2009/01/pseudo-history-countering-cranks.html)

In his book Marxism and Anthropology, which I found really helpful to my own thinking about this subject, Maurice Bloch argues that Marx and Engels had honourable intentions when they tried to deny the presence of stratification and class or proto-class conflict in many ‘prehistoric’ societies. They wanted to show to apologists for capitalism that class-divided, money-obsessed societies are not somehow a reflection of ‘human nature’, and that many human societies have been egalitarian. The trouble is that they, and Engels especially, tried to make this point into a dogma, by taking over Morgan’s simplistic universal stages of human history. I doubt whether there’s a single society which fits tidily into one of the Morgan-Engels stages!

I think that if members of the Workers Party take a look at Patrick Vinton Kirch’s book The Evolution of the Polynesian Chiefdoms, with its incredible synthesis of thousands of sources, its creative use of scientific techniques like DNA testing and carbon dating, its dizzying overview of three thousand years of Polynesian history, and its ability to explain the appearance of both simple and complex Polynesian societies in materialist terms, then they’ll get an idea of what modern materialist anthropology and archaeology really are, and see how impoverished Ray Nunes’ ideas are. That’s not to say, of course, that Kirch’s work is the final word on his subject – each of his books has brought forth a huge amount of argument, and some justified criticisms…

I think the whole Nunes/Morgan thing is a bit embarrassing to be honest, and I don’t think it is a great look for the Workers Party. I myself am an anthropologist, and I’ve known Scott for some years and know him to be rather competent when it comes to deconstructing outdated or psuedo anthropological ideas such as those apparently presented in said pamphlet. I have undertaken research myself into prehistoric Maori social organisation and find many problems with some of the statements presented here, though I feel that Scott has covered them well.

For one, the tone of the writing is a sign of the (past) times – placing ‘Maori society’ into such convienient schemas, as though a homogenous group undergoing some deterministic evolution, reeks of ethnocentricism and paternalism of the worst kind. Anthropology might have once upon a time been seen and used as a tool of cultural imperialism, but has for some time now been reactionary to such ideas.

Daphna states that Morgan lived with the Iroquois for 25 years, as though this argument counters the 150 years of research since which has shown his schema to be far too simplistic. While Morgan may have been an influential thinker, his ideas mark his position in history, not an ultimate law of anthropology.

I also have a problem with using a proviso such as the following:

“Nunes draws on the work, and uses the terminology, of pioneering 19th century anthropologist Lewis Morgan. Morgan in his groundbreaking work developed a theory of stages of society. The terms are largely out of use these days and have pejorative connotations that were imposed after Morgan’s time. While the categories have new names Morgan’s stages are still valid.”

Morgan’s stages are not valid at all! No reading of modern anthropology would come to that conclusion! The statement is to the effect of saying while I aknowledge that this theory is ancient, the theory is still correct. It is hardly critical. In point of fact, 2nd year texts in anthropology and archaeology deconstruct this exact sort of cultural evolutionary schema. Here’s a quote from the Oxford dictionary of archaeology on Morgan:

“… In 1877, Morgan published a book entitled Ancient Society in which he proposed three main evolutionary stages in the development of human societies: savagery, barbarism (in seven substages), and civilisation. This scheme proved popular for a while, although was soon abandoned as being too simplistic.”

Note here that the theory itself is too simplistic, not merely the terms. Morgan’s culture evolution fails on a systemic scale, and any subsequent models or arguments built on top of it will fail for exactly the same reasons (hence Scott’s criticism of Nunes). Further, such culture evolutionary schemas have been outdated since the 60’s – one of the last influential thinkers in the Pacific was Sahlins (though his culture evolution was markedly different and more complex than Morgans), and now such culture evolution has been superceeded by neo-evolutionary theory and new marxist interpretations such as offered by Kirch et al.

If, as Daphna says, other marxists still hold such views then perhaps it is time they reevaluated such views and based them instead on the evidence. Also, I don’t see why modern anthropologists need or should adopt what marxists have to say on the matter at all anyway.

I also have big problems with the claim that the trajectory from Lapita to pre-European Pacific cultures marks a de-evolution in technology. You must have an incredibly narrow scope of technology and culture change if you believe that. What of marine technology, navigational knowledge, horticultural advances, tools? As for the claim that ‘Maori society’ was too rigidly egalitarian to sustain class systems – archaeology shows us that 1) pre-European society on the regional, iwi, and hapu levels were different at different times and at different places 2) that the pattern denotes dynamism and fluidity where groups or communities might come together or fracture depending on extenral stressors and other phenomena (see Harry Allen, 1996). Who is to say that Maori had a static culture without surplus? I don’t think that’s correct.

Perhaps the statement that “without domesticable animals, pottery and access to iron ore for making weapons and tools, the productive forces in a society remain stone age” is the most telling of a lack of anthropological and archaeological knowledge. People tried, and failed, to make that point in the 1800’s. Seem wierd to try and make it in the 21st century!? In fact, it’s so contemptable that it doesn’t even deserve a thorough reply. The ‘stone age’ to use your term, encompasses a huge number of epocs, cultures, technological, and environmental contexts and adaptations from the lower palaeolithic to the neolithic. To lump a relatively modern society in with that vast history because of a lack of pottery and metal tools is far too simplistic.

Finally:

“Scott also claims that modern anthropologists (not the fuddy-duddy traditional Marxist types) no longer view hunter gatherer societies as egalitarian … Maybe it is Scott who needs to get a bit more up to date. Chris Stringer, Britain’s foremost anthropologist in his Origin of Our Species, published in 2011, argues that egalitarianism is what differentiates most human hunter-gatherer groups both from our primate relatives and from agricultural, pastoralist and modern industrialized societies. (p 113).”

I would say that modern anthropologists (of which I am one) might see a tendency for hunter gatherer societies to be generally more egalitarian compared to, say, an industrialised society. However, I’ve yet to meet an anthropologist who would claim any society as completely egalitarian, and the main point is that there are hunter-gather societies who are definately not egalitarian and have relatively high measures of hierarchy or social stratification. I think this is what Scott was getting at. A schema such as Morgans reuires, by necessity, universal laws which, in reality, do not exist.

I think it’s great that Marxists are engaging in the conversation about Maori society and rights. I just think it is a real pitty that the conversation seems to involve only ‘Marxists’ talking amongst each other and not with anthropologists.

“I just think it is a real pitty that the conversation seems to involve only ‘Marxists’ talking amongst each other and not with anthropologists… or perhaps even more importantly Maori scholars themselves.”

Oh, personally I welcome the critical engagement.

Should clarify some of the background to this. Since Redline comrades, the former leadership of the party (including Daphna) departed, we have been revising certain positions over the last year.

At last years’ public conference we began the process of publicly revising our position on tino rangatiratanga, on a panel featuring myself, Bernie Hornfleck and Annette Sykes. We also invited other figures including Ngahuia Te Awekotuku who’s made significant contributions to anthropology.

We would like to deepen the current level of engagement, so we put this up for discussion.

Thanks for the reply Ian.

I was not aware of your recent efforts but those sound very positive and worthwhile. I would find such process within the movement very interesting. The main thrust of my criticism was at the use of cultural evolutionary models in a pubic pamphlet, and some of the odd things Daphna said. I’m glad to hear you want to critically engage with the wider community on this.

But, again, there was no assertion that Polynesian society pre-colonisation was “static” or lacking dynamism, simply that it didn’t produce a regular surplus through regular exploitation. Clearly we need to get more up to scratch with recent anthropology, and I do find Nunes mechanical, but that’s a misrepresentation.

* or perhaps even more importantly Maori scholars themselves.

Hi Ian,

I do think that Nunes’ treatment of Maori society implies that it was fairly static, and destined, in the absence of colonisation, to remain static. Here’s a quote from his booklet (I hadn’t realised it was on the WP site!):

‘If you take the trouble to read Engels’ summary of Morgan’s three stages of savagery and barbarism in Origin of the Family, you will not have much difficulty in seeing that pre-European Maori society was much too undeveloped to reach the highest stage of barbarism, and at best lies at the border between the middle and upper stages of savagery.

The early Maori society was in many ways more highly developed than in most Pacific Islands still, it lacked certain essentials required to reach the middle or upper stage of barbarism, though their primitive agriculture along with advanced (for primitive society) methods of fishing, gives them some features of the lower stages of barbarism. What held the Maori back from further development towards slave society and civilisation was the difference between the natural endowments of New Zealand and the old world.’

Nunes is arguing that the physical environment of these islands meant that Maori existed at a certain level of development, and were doomed to remain there, as long as they remained isolated.

Nunes’ claims that Maori had, at beast, a primitive system of agriculture incapable of generating much of a surplus seem pretty odd, in view of what we know about their horticultural achievements.

Nunes lived for at least the last decades of his life in Auckland, but he seems unaware that the isthmus was, for at least a couple of hundred years, covered in a network of huge gardens.

These gardens made use of all sorts of horticultural innovations, like artificial plaggen soils, specially designed wall systems which created microclimates, and networks of canal ditches. It’s true that Maori, like other Polynesians and like the peoples of the Americas, lacked metal tools and domesticated animals, but they made up for this lack by innovative use of wooden tools like the ko, and by the intensive deployment of human labour (including, in many cases, the labour of slaves).

A tract of old Maori farmland still exists, in the Otuataua Stonefields reserve:

http://www.doc.govt.nz/conservation/historic/by-region/auckland/central-and-south-auckland/otuataua-stonefields/

Even though it covers only a fragment of the old Maori gardens, the Otuataua reserve is still an impressive testament to the scale that Maori agricultural production could reach. Wandering around the site’s hundred or so hectares, one can easily see the extent to which Maori could use technology to modify the landscape and boost production.

If Ray Nunes had visited the Otuataua stonefields, he would also have been able to see evidence for the existence of the concept of private property in Maori societies. At Otuataua and at other large gardening sites around New Zealand, archaeologists have noted how walls and ditches were used not only for horticultural purposes, but also to demarcate the land which could be cultivated by individual whanau. Ian Barber discusses this phenomenon in his essay ‘Of Boundaries, Drains and Crops: a classification system for traditional Maori ditches, NZ Journal of Archaeology, 1989. Contrary to what Nunes claims, iwi tended to have concepts of private as well as collective ownership of land.

The rich gardens of Auckland were one of the reasons the isthmus was so coveted by different iwi. There were so many battles over the place that it was given the name Tamaki a Makarau, or isthmus of one thousand lovers. Chiefs who took control of the gardens could produce and expropriate a surplus which they could plough into trade, war, and self-aggrandisement. Ray Nunes claims that Cook is one of the few reliable sources on pre-contact Maori society, but he doesn’t seem to notice Cook’s many remarks about the sophistication of Maori agriculture, and the size of the surpluses this agriculture could produce. Ian Barber begins his essay by quoting Cook’s comparison of the Maori gardens on the East Coast of the North Island to the plantations of Carolina. When he cruised along the western Bay of Plenty during his first visit to these islands, Cook called the Maori settlements he saw ‘towns’, and Banks thought that they might be the outposts of some great southern continent’s civilisation. So much for the idea that Maori agriculture was primitive, and could hardly produce a surplus…

“If Ray Nunes had visited the Otuataua stonefields, he would also have been able to see evidence for the existence of the concept of private property in Maori societies. At Otuataua and at other large gardening sites around New Zealand, archaeologists have noted how walls and ditches were used not only for horticultural purposes, but also to demarcate the land which could be cultivated by individual whanau.”

Just a note, Marxist definition of private property (capital, very few owners) is distinct from personal property (house, car, garden.)

Marx pointed out how the eroding of personal property, through enclosing land for monied interests, was a key to the development of capitalism – which is surely relevant to the situation here.

Land and slaves, though, can be considered capital, and both were often possessed and used privately in pre-contact Maori society. The provision of individual plots in gardening sites is a reflection of this, as Barber’s essay notes.

Nunes claims that Firth and virtually all other Kiwi anthropologists think that Maori society was capitalist. This is of course a silly misrepresenation of their views. What Firth and many other scholars have pointed out is that there were concepts of private as well as collective ownership and use of land and other capital goods in pre-contact Maori societies. As Kirch’s work shows, this was also the case in other large Polynesian societies.

There’s no question at all that a contradiction developed, and indeed still in some places exists, between Maori collective use of land and capitalism. The Waikato War of 1863-64, for instance, can be considered a struggle between what Gager, Bedgood et al call the Polynesian mode of production, which developed in the 1840s and ’50s and fused some aspects of modernity (a cash economy, the use of markets) with traditional Maori practices, and a pure capitalist mode of production promoted by the Pakeha government. The same is true of the conflict at Parihaka.

Even after the defeats of the New Zealand Wars the anti-capitalist mode of production that Tawhiao and Te Whiti had promoted persisted in places. I’ve blogged about the Bank of Aotearoa and the currency that the Kingitanga created in the Waikato in the 1880s:

http://readingthemaps.blogspot.co.nz/2011/01/recovering-kingdom.html

(the Maori banknotes are pretty cool:

http://2.bp.blogspot.com/_lIWa5EEyxeM/TSPyDOWIxzI/AAAAAAAADPw/dlKUkCxuHqs/s1600/150.JPG)

But you don’t get any of this from Nunes – in his picture Maori society is static, primitive and egalitarian, and then gets flattened by colonisation and capitalism. It’s very similar to some of the patronising and sentimental portraits drawn by Victorian ethnographers and, as Edward says, is a bit of an embarrassment today.

I find Nunes mechanical and dated even for his time. But I think we’re also working from different definitions of class and particularly private property.

From the Communist Manifesto: “The distinguishing feature of Communism is not the abolition of property generally, but the abolition of bourgeois property… [By private property] do you mean the property of petty artisan and of the small peasant, a form of property that preceded the bourgeois form? There is no need to abolish that; the development of industry has to a great extent already destroyed it, and is still destroying it daily.”

Hi Ian,

I’m not sure exactly what point you mean by the quote from Manifesto, but if you’re suggesting that the destruction of pre-capitalist property forms was something that happened automatically, as a result of the establishment of the capitalist mode of production in a society where pre-capitalist modes existed, then I think you’re overlooking not only the history of places like New Zealand but Marx’s own subsequent revision of his views.

Marx certainly believes that capitalism is carrying all before it in 1848, but in his later work he acknowledges that, even in advanced countries like Germany, pre-capitalist modes of production and forms of property can be quite resilient, and can often only be destroyed with massive state violence. He also comes to see that these pre-capitalist forms can have some quite progressive qualities. That’s why he qualified the celebration of the destruction of the pre-capitalist world in his final introduction to the Communist Manifesto, and why he wrote letters to Vera Zasulich and other Russian socialists arguing that pre-capitalist forms like the peasant commune could serve as a basis for socialist construction.

In New Zealand as in much of the rest of the colonised world, state violence was necessary to enable capitalism to survive. As Gager, Bedgood and more recently mainstream historians like Belich have shown, the Waikato Kingdom was thriving in the 1850s and early 1860s, while capitalist Auckland stagnated. The Kingdom’s hybrid modern and pre-modern mode of production saw it outperforming Auckland…this is a good discussion anyway, and it’s interesting to know what your group is thinking and planning on doing.

Not suggesting that, more that pre-colonisation forms of property (which were forcibly destroyed) were not “private property” in the capitalist sense. And yeah, cheers for contributing.

I think Mike’s piece here states agreement with Nunes’s ‘conclusion’ that there wasn’t a regular surplus which would give rise to slave society in terms of historical materialism. In my view that’s essentially correct. I also think that the five stages theory is sound at the lowest (or highest) level of abstraction.

I also think it’s appropriate for us to put this line forward, as I have noticed a kind of rightist snobbery against the concept of ‘primitive’ communism which is determined to paint pre-contact Maori as having a brutish social structure, and this argument is couched in an assumption that those who uphold primitive communism do so from an idealist perspective which paints a ‘rosey’ picture of pre-European contact social structure. I’m not saying that angle is present in the arguments here, but I have definitely come across it in various left-wing discussions.

Aside from that aspect of the article, I’d put forward that I am – whilst quite possibly in a minority – in favour of parralel legal system for Maori. Mostly (i.e. 95%) this is from engaging reasonably thouroughly with Moana Jackson’s work during the course of this year. But actually the tipping point for me was seeing Bob Harvey, former Waitakere mayor, on the TV show Marae Investigates giving full endorsement for the position. Obviously I’m opposed to Harvey and had strong participation in a Workers Party campaign against him. So it’s not a pro-Harvey position. It’s a ‘How did I develop into someone who is politically behind Bob Harvey?’ question.

Cheers, Jared.

Hi Jared,

I think we can point to and celebrate collectivist features of Maori life, both in the pre-contact era and more recently, like the collective use of much land and the collective organisation of labour, without promoting the notion that pre-contact societies were unstratified and didn’t very often have features like a distinction between ariki and commoners, slavery, war, and military conflict. To deny those things is, surely, to succumb to romanticism, given the weight of evidence.

Owen Gager quite rightly criticises Donna Awatere for her attempts to portray pre-contact Aotearoa as some egalitarian paradise in her early book Maori Sovereignty. He points out that this image is beloved of rightward-moving Maori nationalists – bourgeois nationalists, to put it crudely. Although I support a lot of what Hone Harawira does, he’s unfortunately in the habit of perpetuating the portrait Awatere created. And Hone’s false image of pre-contact societies leads him sometimes to make quite reactionary comments:

http://readingthemaps.blogspot.co.nz/2010/08/hones-racism-was-made-in-europe.html

I don’t really think we can salvage much from Morgan’s stages by appealing to them as imprecise abstractions. As Edward says, they were intended as universal laws, and if a universal law is contradicted by instances it doesn’t cover then it is in trouble. The Morgan-Engels stages are contradicted continually, and it’s very hard to see how any researcher could use them to understand Polynesian society.

One of the egregious aspects of the Nunes passage I quoted upthread is its suggestion that other Polynesian societies were less developed, and had even less of a surplus, than pre-contact Maori societies. I wish Nunes were alive, so we could take him up to Tonga or Samoa, never mind Hawaii or Tahiti, and show him the monumental chiefly and religious architecture there! How did the Tongans build scores of immense funerary monuments in their ancient capital Mu’a, not to mention dig canals for ships and build stone wharves there, if their productive forces were very limited, and they couldn’t muster much of a surplus? I think Nunes decided that Polynesian societies like ancient Tonga couldn’t have existed, simply because they didn’t fit in with the Morgans-Engels stages (because they didn’t have metals, for instance). A schema which forces someone to so completely evade reality is not an aid to understanding – it’s an intellectual straitjacket.